From The American Enterprise Institute:

Populism, American Style By Henry Olsen

National Affairs

Monday, June 21, 2010

On February 19, 2009, business journalist Rick Santelli inadvertently helped launch a populist movement. Appearing on the cable network CNBC from the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, Santelli spoke of rising public anger about the expensive taxpayer-funded bailouts of failed banks, bankrupt corporations, and home owners who had defaulted on their mortgages. These policies were breeding deep concern about the growth of government, Santelli argued, and people were looking for ways to express their opposition. "We're thinking of having a Chicago Tea Party," he said, suggesting that participants might throw stock certificates into Lake Michigan.

The tone and substance of Santelli's complaints struck a nerve. Video of his remarks spread rapidly across the internet, and his reference to the Boston Tea Party seemed to give many the inspiration they were seeking. Just two months later, on April 15, an estimated 500,000 people marked tax day with roughly 800 "Tea Party" protests across the country. There have since been hundreds more such gatherings, including several large demonstrations in Washington and other major cities. Directed especially against the Obama administration's economic policies and the recently enacted health-care legislation, these events represent a large (if loosely organized) grassroots protest movement. Indeed, this past April, a New York Times poll found that 18% of Americans identify themselves as Tea Party supporters.

American populism, as it has taken shape again and again throughout our history, has not yielded the demagogic figures that so worried the classical philosophers.Yet as this new populism has spread, it has also generated a great deal of worry and disdain. One might expect a negative response from observers on the left: Tea Party anger is, after all, directed at their favored policies and politicians. But the Tea Partiers have also engendered concern and scorn among many on the right and in the center. New York Times columnist David Brooks, for example, has defined the activists as "a large, fractious confederation of Americans who are defined by what they are against," and who are characterized by the "zero-sum mentality that is at the heart of populism." Washington Post columnist George Will, who opposes many of the same policies the Tea Parties reject, has his doubts, too: Populism's "constant ingredient has been resentment," he wrote recently. "It always wanes because it never seems serious as a solution."

This dim view of populists has a long pedigree in political thought. Observers since Plato and Aristotle have warned that democracy's peculiar failing is its tendency to produce demagogues: popular leaders who can excite the masses through fiery oratory, and then exploit the resulting political fervor to rise to power and destroy the state.

The American founders had the same fears, and so built our republic to contain such outbursts whenever they might arise. By and large, they have succeeded: American populism, as it has taken shape again and again throughout our history, has not yielded the demagogic figures that so worried the classical philosophers. Our exceptional nation has an exceptional political culture, and among its foremost features has always been a distinctive form of populism that, far from threatening to destroy the republic, has at crucial moments helped to balance and rejuvenate it.

This is not to say that we know for sure what our own populist moment will bring. To understand both its significance and its potential, however, we should look not at the classical portrait of populism but rather at its unique manifestation in the United States--a history that is, by turns, both consoling and cautionary.

The Specter of Demagogues

Our view of classical populism is shaped by both the warnings of philosophers and the experiences of some democracies, ancient and modern. In the Politics, Aristotle defines a demagogic democracy as one in which "the decrees of the assembly override the law" and a popular faction "takes the superior share in the government as a prize of victory." The people's leader, the demagogue, incites them to pursue such despotism through extravagant rhetoric, playing on the people's basest desires and fears. The result is laid out ominously in Plato's Republic: The people--"an obedient mob"--"set up one man as their special leader...and make him grow great." The masses take the property of the wealthy to redistribute it among themselves; the people's enemies, meanwhile, are charged with crimes and banished from the city (or worse). The Athenian philosophers were not merely theorizing such scenarios: Their city had lived through them, during the reigns of the 5th century B.C. demagogues Alcibiades and Cleon.

Though classic populism has varied according to time and place, it has generally taken the form of a morality play in four acts. In the first act, the masses come to feel like powerless victims, left helpless against the onslaught of an oppressive "other." In the second act, often following a crisis, that "other" is defined by a popular leader as an implacable enemy--one who has no concern for the welfare of the people, and whose actions are motivated by selfishness and greed. In the third, the leader proposes a solution: The people must use their numerical advantage to seize control of the state. In the final act, that power is used to take back from the enemy that which rightfully belongs to the people, without regard for the enemy's consent or rights.

America has never had a classically populist regime. More interesting, however, is the fact that--contrary to Madison's assumption--the demand for such populism has always been fairly low in America.This basic outline has been followed by regimes throughout history--from the demagogueries of the ancient Greek democrats, to the modern forms of communism, fascism, and socialism. The enemy can be economic (like capitalists or aristocrats), racial (as the Jews were for the Nazis), religious (as with sects in Lebanon or Iraq), or foreign (think Hugo Chávez's denunciations of America). The circumstances of each case differ greatly, of course, but the pattern remains the same: The "victim" seeks to vanquish the "victor," to take what is rightfully his, and to do unto the other what has allegedly been done unto him. When the drama is finally over, the rule of the people has given way to the rule of a despot.

Such a pattern was among the evils James Madison sought to contain through the Constitution. His great fear, as he put it in Federalist No. 49, was that "the passions,...not the reason, of the public would sit in judgment." If this were permitted, Madison wrote in Federalist No. 10, "the influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame"; the American republic, he believed, should be designed to keep such conflagrations in check.

Madison assumed that Americans would be tempted to demand classical populism; the challenge was to reduce the ability of the government to supply it. In this sense, his creation has clearly worked: America has never had a classically populist regime. More interesting, however, is the fact that--contrary to Madison's assumption--the demand for such populism has always been fairly low in America. As it turns out, Americans have tended not to launch large-scale quasi-democratic movements in the classical-populist mold. And when such movements have arisen, they have generally not done well at election time--and so have never come close to enacting their agendas.

The relative absence of these movements has always puzzled European and Marxist social scientists, who have struggled to explain why America--in this respect virtually unique in the Western world--never formed a significant socialist or communist party. After all, economic mobility isn't that different in the United States than in Europe. Inequality is worse. Why, then, haven't Americans clamored to overthrow the powerful? What is the matter with Kansas?

The answer is to be found in the American soul, shaped as it has surely been by Madison's system. Americans are a self-governing people through and through, and American populism reflects the American passion for self-determination. That passion certainly leads some Americans to respond powerfully against overbearing elites, and so causes some populist movements to form. But it has also often allowed these responses to be channeled in constructive directions--keeping our politics in balance, and over time giving rise to enduring political coalitions.

In looking at some key populist episodes in our history, then, one finds a pattern that should ease the worries of those now concerned about a politics of resentment. It is also a pattern that offers some crucial guidance for the instigators and cheerleaders of today's populist movement. . . .

The full text of this article is available from National Affairs.

Henry Olson is the Vice President and Director of the National REsearch Initiative at AEI.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

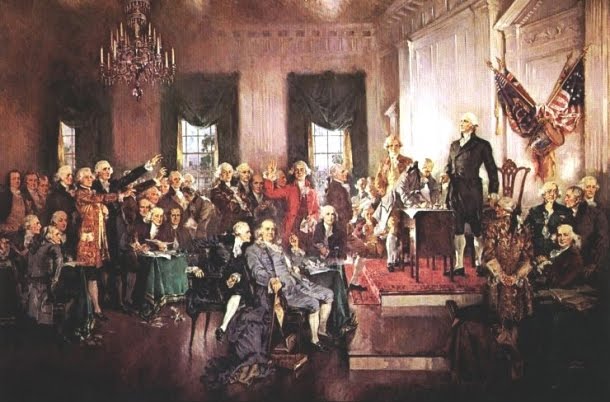

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment