From The New Ledger:

The Business Perspective on Dodd-Frankby Francis Cianfrocca

The many instant analyses of Dodd-Frank which appeared in the media are much like the legislation itself: they focus on the minutiae. None other than Dodd himself said that his law is so complex that no one can predict how it will actually work until after it’s been out there for a while.

With this, Dodd was perhaps acknowledging that banks, broker/dealers and investment firms will find creative ways to circumvent the hundreds of arcane provisions in the law, thus largely diluting their impact, and also incidentally creating new imbalances and distortions which will certainly play out in the next crisis. Dodd may also be thinking of the relentless sausage-making that went into this law, which seeks to appease an angry public, but also to appease Wall Street itself, the industry that DC politicians fear as they fear no other. While mainstream press outlets professed surprise that the stock prices of financial companies leapt upward on word of the conference report last Friday, real market participants understood instantly that this law could have been far, far worse for the industry than it turned out to be.

Dodd-Frank’s most egregious omission is that it does nothing at all to change the status of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These are the monsters that channeled a maelstrom of malign influences, to produce the still-ongoing housing bubble. When Fannie and Freddie entered government conservatorship in September 2008, the enabling legislation noted that, ideally, they would be unwound rapidly and soon cease to exist. Very shortly afterward, Barney Frank himself explicitly disavowed any such notion.

ADVERTISEMENT

Today, Fannie and Freddie are larger and weaker than ever, accounting for some 95% of all newly-written mortgages, and representing a $5 trillion asset base that, investors understand, is now fully if implicitly guaranteed by US taxpayers. US housing is still in such a fragile state that Congress dared not expose Fannie and Freddie to market forces or to force them to restructure. From September 2008 until today, they’ve sucked down about $145 billion in bailout funds, and each continues to lose about $10 billion per quarter. This is the ongoing cost to taxpayers of artificially supporting US housing. Nothing has changed, and the abusive and hyper-risky behaviors of the bubble years continue to this day, albeit in attenuated form.

It’s impossible to say much about the consumer protections in the Dodd-Frank legislation, because they’ll be created and enforced in a fragmented way. The regulators will have over-regulators that can strike down rules they don’t like. Much was made of this segment of the law in the popular press, because it’s imagined that financial products really are constructed in order to prey upon hapless consumers. But American individuals are now in an extended and historically-unprecedented pattern of reducing their overall indebtedness. This extremely important and underreported development means that the new consumer protections, such as they are, will have relatively little impact on the behavior of either borrowers or lenders. Just try to go out and ask your bank now for a no-doc “liar loan” with a tiny down payment. You won’t have any luck, with or without Dodd-Frank.

What about the curbs on the risk-taking activities of financial intermediaries like banks and investment firms? I could write a very long and boring post on this subject, but others have done that already. It really needs to be said, however, that the activities of these firms, which turned out to create unhedged systemic risk on a biblical scale, actually were perceived as low-risk activities by their practitioners. Because of forces like globalization, there has been no profitable business model for traditional banks for nearly twenty years now. They can only be profitable if they dial up the amount of risk they take or the leverage they use. Financial innovation indeed allowed them to package up risk into liquid and easily-tradable units. Liquidity itself is an extremely valuable thing in ordinary times, but it greases the skids in crisis times.

This is something which remains true today, and Dodd-Frank does nothing to change it. What we see now is that the largest industrial companies largely fund themselves directly in the capital markets. They’re not strongly affected by the widespread undercapitalization of the banking industry. But that undercapitalization does strongly impact small businesses, who now have very restricted access to bank finance and are thus largely unable to grow and create jobs. If anything, Dodd-Frank (together with the Fed’s zero-interest-rate policy) creates further disincentives for banks to act as financial intermediaries.

Meanwhile, the proprietary risk-taking activities of banks, broker/dealers and investment firms have been curtailed very little, and in ways that will not be hard to circumvent. There is tremendous attraction in continuing these activities, because the industry is now more concentrated than ever, and benefits from extremely low-cost capital arising both from zero interest rates, and from the government’s demonstrated unwillingness to let major institutions fail.

Some of these measures, like the new restrictions on capital adequacy and retention of risk, are small steps in the right direction. I would have preferred much, much more of this kind of change. Bankers were able to weaken these rules by objecting that they would make banks less profitable. (Stifle the urge to exclaim “Well, so what?!”) What bankers really want, though, is avoid being made less profitable on a risk-neutral basis. The job of finance is to convert savings from investors into capital for business. For centuries this process has been about the prudent measurement and management of risk. Nowadays, the practice of banking is more about enjoying the upside while transferring the downside to the taxpayers. The new law strongly abets this pernicious business model.

That leads to the most salient criticism of Dodd-Frank: it cements in place the existing constellation of too-big-to-fail institutions. We indeed have created a system of “utility banks,” making near-guaranteed profits from a set of implicit and explicit rules that prevent large-scale changes in the structure of the industry, or indeed of individual institutions, in which government officials have made tremendous public investments.

Dodd-Frank’s new rules will certainly impose some inconvenience, regulatory uncertainty and operational inefficiency. But by no means will they produce the changes that most Americans deem to be the most needed. Banking will remain an egregiously overcompensated business; guaranteed multi-million dollar bonuses will remain the standard practice; and banks will remain fully insulated from failure while leaving the system unbalanced and vulnerable to the next crisis.

And bankers will have less incentive than ever to engage in the kind of proper risk-taking behavior that could actually produce a strong economic recovery.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

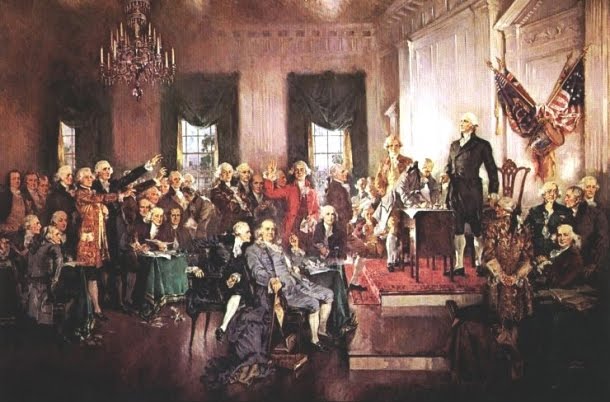

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

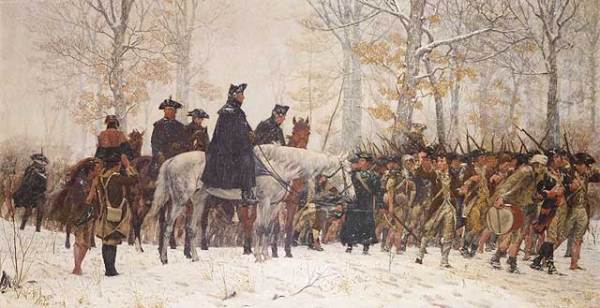

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment