From The American Enterprise Institute:

Current Regulatory Developments in the United States We Are Repeating the Missteps that Contributed to the Financial Crisis

By Paul S. Atkins

Global Financial Services Centres Conference

(June 27, 2010) This speech was delivered at Fintel's Third Annual Global Financial Services Centres Conference in Dublin, Ireland, on April 27, 2010.

It is a great honor and privilege for me to be here with you today for this 2010 Global Financial Services Centres Conference. This is actually the third time that I have had the honor of addressing conferences here in Dublin Castle. The calibre of the content and organization is as distinguished as in years past. It is a pleasure to be here to participate in the discussions.

In the year and a half since I left the SEC, I have watched with increasing dismay the drift of things in Washington and the rest of the world. The debate regarding financial services has devolved to politics, rather than a focus on sound policy that will foster a robust financial sector able to achieve what its ultimate mission should be: raising capital efficiently for the "real" economy of businesses creating goods and services, and thereby jobs. In the US, politicians are frightened over an almost certain backlash by voters in November. Regulators seem concerned mainly with headlines, pandering to the politicians through poorly conceived enforcement actions and through politically motivated rules. SEC Commissioner Kathy Casey aptly described one of them recently as "regulation by placebo".

What a time you have picked to have a financial services conference! In Washington this week, the US Senate is taking up a financial services bill that is more than 1,300 pages long and sweeping in its scope. It will cost the American taxpayer billions of dollars and will create whole new bureaucracies staffed with thousands of people. These bureaucracies will endure and grow decades into the future. The bill is a poorly drafted hodgepodge of provisions, most of which have nothing to do with the financial crisis of the past few years. To that point, Congress set up last year the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, of which the previous speaker, Peter Wallison, is a member, to study and report on the causes of the financial crisis. Do you think that the members of Congress would wait for that study to come out and get the full value of the taxpayer dollars that they committed to that effort? The answer apparently is "No."

This situation reminds me of the story of an American commuter who was as usual rushing late to work after a long night out with the boys. When he got to his workplace, all the parking places were taken. He kept circling the parking lot and then said: "If only I could find a parking space, I’ll repent and start a new life: go to church, give up the drink, and reconnect with my family." Boom. Suddenly a parking place miraculously appeared. What did our commuter then say? "Oh, never mind; I found one."

After making it through a wrenching crisis and finding that things are looking better than they did in the autumn of 2008, leaders of the G-20 nations seem like that commuter--going back to business as usual. Now that the world economy may have turned the corner at least temporarily, the danger is that politicians will not bother to learn the proper lessons of the causes of the financial crisis and will sow the seeds for the next crisis. They will just take as given in the popular narrative, legislate accordingly, and move on. The true problems will fester and lead to the next crisis.

Today, I plan to talk about several trends and events that led to the crisis, some of the developments in Washington in reaction to the crisis, and the hangover effect that will take years to work out.

There certainly are multiple, complex, and interrelated causes, which have been decades in the making. These causes are more than the competence or incompetence of individuals in particular roles, but have more to do with fundamental principles of organizational and market behavior, specific regulation, government subsidies in housing finance, and incentives or disincentives built into the system.

The danger is that politicians will not bother to learn the proper lessons of the causes of the financial crisis and will sow the seeds for the next crisis.Peter Wallison, whom I am very proud to say is a colleague at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, has already given an excellent overview of what has happened in the past few years. The housing crisis in the United States, which had so grave effects around the world, was not created in a day. Short-sighted political calculations made over decades by people with little or no knowledge of economics and human behavioral psychology led to the consequences that we live with today. Your own housing bubble in Ireland had unique features of its own.

We should not forget that one contributing factor of the events of the past few years is, ironically enough, simply put--freedom. In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell and more than two billion people in the next few years in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and China--plus India as it liberalized its own economy--joined the world system of trading and commerce that had developed after World War II. With all of these new workers, the world became more productive than ever and business and finance boomed. Advances in telecommunications and information technology revolutionized the way of doing business, especially in financial markets. So, this huge productivity and growth in efficiency created new wealth, because money after all is not printed, it is created through people being productive, using their brains and hands to make things and do things that other people want and need. That is the essence of commerce, and it took some time after 1989 for that productivity to work its way through the global economic system, inceasing capital for investment.

The growth in available capital and the increased productivity in the world economy manifested itself in a stretch of relatively low real interest rates. How many times did we hear the phrase, "too much money chasing too few good deals"? The laws of supply and demand work in the capital markets as in any other market. Of course, low interest-rate/easy-money policies of central banks threw fuel on the fire. In the United States, these policies arose from economic concerns regarding Y2K (remember that one?), the terrorist attacks of September 2001, fears of deflation, and other issues. Asset prices rose, credit spreads narrowed, and the perception of risk in financial instruments tied to appreciating assets diminished, which then encouraged financial institutions to increase leverage. Low yields on financial instruments led investors to seek better returns. That is why AAA-rated paper, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac securities, with higher yields than government bonds, was so popular.

Don’t worry; I will not go into all of the rest of the story that you know too well. Similar to your experience here in Ireland, by some estimates the US government wound up having more than $15,000 to 20,00 billion (in American English, that is $15-20 trillion) of exposure to the financial system (depending on how you count) through various programs, including more than $7,000 billion alone in guarantees for the government-sponsored entities of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (and this number is still climbing), some $3,200 billion in money market mutual fund guarantees (which the mutual fund industry did not want and was never in fact used), another $2,500 billion added to the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet through the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility ("TALF" for short) and other programs, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (TLGP) at almost $1,500 billion, and finally the Troubled Asset Relief Program ("TARP") for a comparatively small $700 billion.

Besides government housing policy that Peter Wallison discussed so well earlier, I think that the turmoil in the financial markets in 2008 can be boiled down to three causes: the special role attained by the credit rating agencies (mainly through government regulation), lack of transparency of balance sheets of financial services firms, and the flawed implementation of mark-to-market accounting.

The turmoil in the financial markets in 2008 can be boiled down to three causes: the special role attained by the credit rating agencies (mainly through government regulation), lack of transparency of balance sheets of financial services firms, and the flawed implementation of mark-to-market accounting. First, with respect to mark-to-market accounting, much ink has been spilled over its good points and flaws. It is pretty hard to argue that historical cost accounting is the way to go. On the other hand, the idea that accountants can somehow be turned into omniscient beings and psychologists who can divine non-market values for tangible and intangible assets is a truly unworkable expectation. Then, in the financial crisis accountants understandably were unsure of what to do when markets disappeared. They were also worried about their liability at the hands of the trial lawyers and second-guessing regulators. It literally took the threat of an Act of Congress to get the SEC and the Financial Accounting Standards Board finally to act in September 2008 by adopting what I for one had advocated earlier that year--clear guidance to accountants that in the absence of an orderly market they can use other means to figure out the value of an asset.

Second, if financial statements lack transparency, investors will lack confidence. That is a pretty simple concept. The bank regulators exacerbate this situation because they believe it best that the true financial condition of a bank not be known to the public. They are trying to prevent runs on banks, so in the name of safety and soundness of the financial system, they believe in maintaining a degree of secrecy. Basically, they are relying on government deposit insurance programs to keep depositors calm.

The trouble is that investors in banks are not helped that way. The TARP infusions, other than demonstrating that the government was willing to put taxpayer money on the line and stood ready to bail banks out, did not solve the transparency issue. In fact, the transparency issue persists and affects valuation of financial firms. It did not help that the government at first claimed that TARP money would only be given to "healthy" banks. This claim proved to be manifestly false as even some of the original recipients appear not to have been healthy. The valuation of financial institutions began to improve only after the results of the government-administered stress tests, for all of their flaws, were published.

Last, but not least, are the credit rating agencies. Starting in 1975 by way of the Net Capital Rule, the SEC granted some credit rating firms special status as so-called Nationally Recognised Statistical Rating Organisations, or "NRSROs". Partly as a result of this special designation, from which commercial benefits flow, the rating agency industry over the years has become an oligopoly--three large firms control 90% of the market, and two of them control 80%. In fact, until Congress passed the Credit Rating Agency Reform Act in 2006, which finally set out an open, coherent regulatory regime for NRSROs in the United States, the SEC’s staff had applied an informal, non-transparent process to grant NRSRO status. This designation process was frustratingly slow and had the effect of limiting competition in issuing credit ratings. Congress had the right idea to force the SEC’s hand to open up the process, but unfortunately for the American taxpayer, it did not come soon enough to affect the state of the market.

The problems with collateralized debt obligations made it clear that many investors relied on credit ratings without performing their own due diligence. Government agencies relied on credit ratings to their detriment as well. So, even if conflicts of interest are addressed and fully disclosed through the legislation and rules, we still have the problem that opinions of certain institutions are given great regulatory weight. Thus, few realized the great systemic risk inherent in the holdings of CDOs by financial institutions, because they were deemed to be the highest-rated instruments.

Would more voices in the rating industry have averted the problems with ratings of structured products? That is an interesting question that can be debated. Clearly, the existing oligopolistic system did not work.

You can see that one general theme today is how the unintended consequences of government policy and regulation affect the markets. One cannot view government programs only in the short term; one must take into account the longer term. Otherwise, the analysis inevitably will be superficial because the full ramifications of decisions are given little weight.

The United States Congress has already held several hearings regarding the financial crisis. The Administration last year proposed a major bill (rivalling the health care bill in length). The House of Representatives passed several bills in response. Senator Dodd, the chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, has a 1300-page bill now under discussion in the Senate. This legislation, if enacted, will make sweeping changes to the financial services regulatory environment.

The current proposal in Congress is a discouraging grab-bag of special interest pleading and wrongly conceived purported "solutions" to conditions that led to the financial crisis. What we need is careful analysis to determine how we can efficiently and effectively promote honesty and transparency in our markets.

You can hear many voices now proclaiming the so-called "death of capitalism" or that supposed "deregulation" during the past 4, 8, or 10 years led to the crisis. One can hardly say that the past 8-10 years have been deregulatory. In the United States we had Sarbanes-Oxley, new SEC rules, new stock exchange and brokerage rules, and new accounting rules.

The problem was that many of these rules were not aimed at the correct risk points of the system. Worse, they were distractions from the main issues. That is the inherent problem with regulation. It is a blunt instrument at best, and subject to the frailties of the human regulators. If the regulator does not use an effective cost/benefit screen to analyse its proposed rules properly, or does not listen to public comments as to efficacy or unintended effects, or tries to regulate through enforcement with its inherent unpredictability, the consequences can be inconsistent, distortive, and not easily corrected. We must remember that investors ultimately pay for regulation. If regulations impose costs without commensurate benefits, investors suffer the costs of lack of effectiveness and efficiency, not only through higher prices but also through constrained investment opportunities. That ultimately hurts them in their investment performance, because it means less opportunity for diversification.

For example, economists and many at the SEC accurately point out that fees paid by investors to asset managers and brokers can negatively affect their long-term return, so investors should take those fees into account in their decision-making process. Likewise, regulatory costs can negatively affect an investor’s long-term return, but the investor usually has no choice but to bear this cost. Thus, the government must be very careful in imposing those costs and rigorously draw a cause-and-effect relationship between the costs and purported benefits.

No, supposed "deregulation" is not the reason that we are in the current situation. In fact, I think that this attitude that blames our current problems on "deregulation" is not only completely wrong, but dangerous. If that is what policy makers think is the reason for the current situation, then they have learned the wrong lesson and their solutions will cause more problems than they will solve. We are still living with the distortive effects of some of the laws passed 75 years ago in the wake of the 1929 market crash. The problem with some of these laws was that instead of focusing on problematic practices and addressing them directly, the government reshaped the entire industry with negative consequences that endure to this day.

More regulation, for regulation’s sake, is not the answer. We need smarter regulation.For example, Congress passed the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 because of self-dealing and manipulation in securities of interstate utility holding companies in the1920s. Instead of focusing on the problematic practices and addressing them directly, Congress reshaped the entire industry and in the process Balkanised power generation and transportation in the United States. By the end of the 20th century, the Act was cited as a reason for a relative paucity of investment in the American electric and gas utility industry. What were the unintended consequences? After Congress repealed the Act in 2006, for example, alternative energy technologies are easier to finance and new capital has been attracted to the utility industry. What would our power industry be like today if a different legislative strategy had been pursued originally?

More regulation, for regulation’s sake, is not the answer. We need smarter regulation. Regulators need to understand the limits to their effectiveness and where their actions can cause unhelpful distortions. Some are saying that we need to trust less in the marketplace and more in the brilliance and perspective of regulators. With all due respect, I do not think that regulators will be able to be effective systemic risk identifiers. Larry Summers, who is now the president’s chief economic advisor as head of the National Economic Council, wrote two years ago in the Financial Times (before he entered government) that regulators supposedly should be able to foresee bubbles and intervene to stop them. Well, that’s much easier said than done. And, even if this crop or future crops of people with regulatory authority are smart enough or lucky enough to head off a bubble--and bear the political heat for doing that (because one man’s bubble is another man’s bread and butter)--how can you build public policy for years in the future on the hoped-for omniscience or luck of independent, non-elected, unaccountable regulators?

This global crisis has primarily affected regulated (versus non-regulated) entities all around the world, not just in the supposedly deregulatory United States. How did so many regulators operating under vastly different regimes with differing powers and requirements all get it wrong? Indeed, how did so many firms with some of the best minds in the business get it wrong?

I am asked all the time what did lead to failures at the SEC and other regulatory agencies--both in the United States and globally--to discern the increasing risk to financial institutions under their jurisdiction. How did we arrive at this situation, particularly in the United States? I believe that part of the answer is the failure of leadership and distraction of regulators by false priorities. My discussion will focus mostly on the SEC, since I know it the best.

A number of corporate accounting frauds, especially at Enron and WorldCom, which came to light after the stock market peaked in 2000, caused Congress to pass the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, and in particular its section 404, which requires that publicly listed companies undertake a formal internal controls assessment and have that certified by independent auditors. Congress imposed these rules even though they would not have prevented an Enron or WorldCom in the first place, because those were not internal control problems, they were top-down collusions to commit fraud by management and auditors. But, nonetheless, public companies ultimately spent huge sums on documentation of internal controls. Did some good come out of this enormous expenditure? Probably some, because I imagine that some companies found holes in their internal processes or redundancies that could be streamlined. But, was the enormous cost and internal disruption caused by this market-wide edict worthwhile to shareholders? Did the huge crush of paperwork and process distract boards and management from the truly important business and risk management issues? Most importantly, could the financial crisis have been averted (or at least the worst effects blunted) if board members and management had spent more quality time on the real issues rather than on a paper chase?

Then, we had a number of distractions at the SEC. Chairman William Donaldson in 2003 to 2005 pushed through three major controversial rules regarding mutual fund governance, hedge fund registration, and the so-called National Market System rules. These rules were reactive to scandals or perceived problems. In these cases, the SEC never conducted an adequate analysis of the costs versus the benefits of these proposed rules. The hedge fund and mutual fund rules were invalidated by the courts after long litigation and much distraction for the agency and the industry.

I go through this catalogue of regulations to give you an idea of what went on during the past 7 years, much of which sounds now so trivial in light of the current situation. Life is full of choices and opportunity costs. If you devote resources to one thing, you have less to devote to another. And, the one risk that you have not focused on just may blow up in your face.

That, in fact, is just what happened to the SEC. During this critical 2003-2005 time period when so much effort was wasted on these quixotic detours, the market for collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) was taking off. No one seemed to notice, or when they did, they consoled themselves that these instruments were highly rated, mostly backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac securities. The major problem was the increasing lack of diversification, which traces itself to the overreliance on NRSRO credit ratings.

In this context we have a financial services bill being debated in Congress. This proposed financial services legislation contains many troubling provisions. The very nebulous idea of a systemic risk regulator and its inherent notion that some firms (supposedly undisclosed to the marketplace) are too big to fail is a recipe for future disasters like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They and the market will know that they have an implicit government guarantee. The legislation would basically codify the ad-hoc steps that the Treasury and the Federal Reserve took in 2008 with respect to the various bail-outs. The proposed Consumer Financial Products Agency could well turn into a merit regulator, deciding on the suitability or merit of products for sale to different classes of investors. Just think. Apple Computer went public in the early 1980s when many state securities administrators had the power to approve of securities for sale in their states. Believe it or not, the Apple IPO was banned in Massachusetts because a state bureaucrat thought that the company was not a good investment for the citizens of his state. I am sure that Massachusetts investors were happy that their government was there to help them.

I fear that this Administration and Congress are leading us back in the direction of merit regulation in the financial services industry.

This Administration is basically advocating "Stability über alles". In the words of the Secretary of Treasury, the goal is for markets that are "more stable, safer, and less prone to crisis." Well, that may be a great goal, but it is completely unrealistic. The marketplace is messy because it reflects humanity at its basic level, filled with emotion, rumor, fear, and greed and is not easily containable. Do we want to try the failed idea of central planning again? How will government officials with clearly imperfect information possibly oversee capital across industries and countries, magically setting capital standards for financial institutions?

Regulators cannot see into the future any better than anyone else. Even worse, they have political considerations to deal with and have no ready mechanism to guide their actions. Their track record for the past 100 years at foreseeing systemic risks has not been good at all. Even if they do identify a risk, the political realities make taking effective action daunting.

Well, we are certainly in the middle of a great debate, with huge consequences for investors and the financial services industry.

But, with great change, great opportunity also exists. You have been a most attentive audience. Good luck with your navigation of this environment. I look forward to our panel’s discussion.

Paul S. Atkins is a visiting scholar at AEI.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

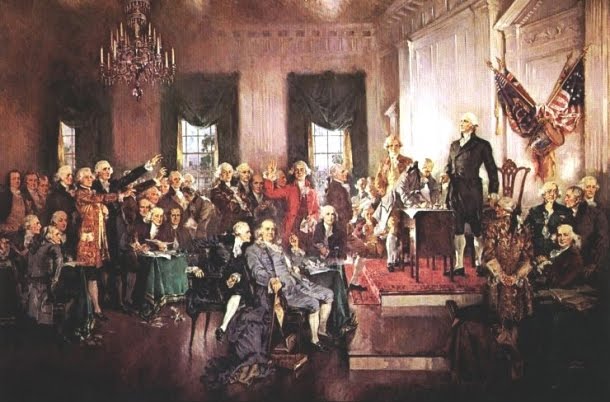

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

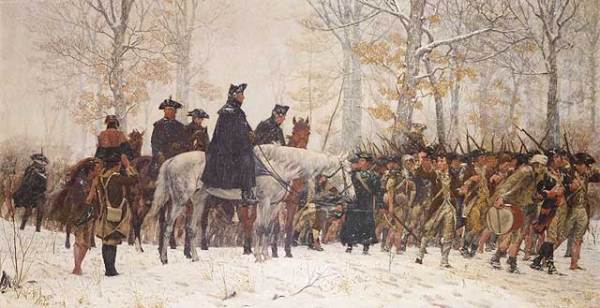

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment