From The New Ledger:

The Coming Big-Deficit PR Campaignby Francis Cianfrocca

Well, look, you’re going to be hearing an awful lot about this as the summer drags on toward the midterm elections, so we may as well get started: our leaders (if you’ll pardon the expression) will be trying to sell us on much higher deficit spending over at least the next two years.

The popular case against an aggressive borrow-and-spend policy is the one Congress cares about, of course, since it’s going to influence votes this fall. It’s also the simplest and easiest to dispose of. It boils down to “You can’t spend your way out of trouble.” This is indeed the right attitude for consumers, particular those deep in debt and worried about losing their jobs. But it makes no sense in macroeconomic terms. We’ll come back to this point.

The case for deficits, in the oversimplified way that noted economics expert Joe Biden and his sidekick Barack Obama will be making it this summer, comes down to: “The stimulus package we passed last year prevented another Great Depression! Don’t you want more of what makes you feel good?”

ADVERTISEMENT

The case made by advocates is more sophisticated and has more to recommend it. We know that economies turn, because they always do (pay no attention to that island nation in the Pacific that makes the cars you drive). We’re not 100% sure that public demand actually causes private economies to recover robustly, but we don’t really need to answer that question definitively.

We do know that millions of people are hurting because of high unemployment. This produces some terrible effects with long tails. For example, young people starting their careers in a jobless market risk taking a permanent hit to lifetime earnings, because your early jobs set the tone for the pay raises you get farther down the line. And of course the corrosive social effects of chronic unemployment are well-known.

Ok. I can bite off on expanded deficit spending to mitigate these problems. But I’m a lot less sympathetic to the argument that bailout are needed for the 50 states. People on the left need to be very careful pushing this argument, because many local governments are so corrupt and politically craven that they could really benefit from some forced fiscal discipline. And voters are starting to wake up to this. Big corporations went out of their way to earn the public’s mistrust, but government is no slouch in this department either.

The other key point being made by the neo-Keynesians is very simple: long-term interest rates are low and not rising anytime soon. This leads to the following argument (with apologies to Augustine):

“Lord, give me fiscal discipline, but not yet. We need to keep flooding the economy with borrowed money until the economy turns. When that finally happens, the Fed will suddenly find itself back in that happy place where it can manipulate the economy with changes in short-term interest rates.”

It’s odd that you hear this even from people who thought the “Great Moderation” of the past 30 years was fraudulent. What these people are saying is that normalcy is coming, maybe two or more years from now. When unemployment falls as it inevitably will, we can have a negotiation between the Fed and Congress: we’ll trade off higher taxes (which will cut the deficit spending) against lower policy interest rates (which will keep the economy from collapsing again under the higher taxes).

There’s no small amount of wishful thinking in this (and I won’t even touch the anti-incentive effects of the higher taxes). For one thing, there’s an assumption that the economy will return to growth by magic. After all, it always does. I’m sympathetic to this point, of course, because it’s never a good idea to argue against observed reality. But there’s another observed reality in the mix, which is Japan. They suffered an extreme balance-sheet recession with deflation, and went to exceptional levels of public deficits with barely any effect.

When I make this point, people immediately say “Oh but you’re so full of [excrement]. Don’t you know that the US is different from Japan, for reasons A, B, and C?” The same people, of course, will tell you know that they understood the financial crisis before it happened. Then when you ask how much money they made trading against it, they shuffle their feet and get quiet.

The other problem is that there’s no visible pathway to an uptick in consumer demand, as there was in past recessions. The impact of a vast reduction in private credit available to consumers is going to have unknown repercussions that could easily surprise on the upside or the downside. And a vast transformation in global investment patterns is now underway that could put a permanent drag on income growth in the US. (Standard economic theory here holds that sound investments elsewhere in the world will produce gains here. This assumes both free trade and the soundness of other people’s investments. Not necessarily good assumptions.)

And those are the proximate factors. The longer-term problem is a huge need to rebuild capital in the wake of the crisis, both among individuals and among banks. This is a structural pull toward deflation. It may turn out that the Augustinian period of fiscal undiscipline being urged by Keynesians will last a whole lot longer than they expect.

So look, what should we do differently? I’m going to save for another day a full analysis of the counterpoint, notably expounded by Alan Greenspan last week in the WSJ, which is that you really can’t predict long-term interest rates. Nobel-Prize winning economists may believe in their models, leading them to predict low market rates for as long as it takes the recovery to magically arrive.

But anyone who has been around markets rather than economics seminar rooms knows how foolish this is. More than foolish: dangerous. If our strategy for recovery assumes low market rates, how quickly can we pull out, and at what cost to the economy, if rates suddenly move against this trade? Maybe Blanche Lincoln shouldn’t be so eager to outlaw credit-default swaps. She may need a few, written against the US Treasury.

Let me meet the Keynesians halfway. Let’s recognize that long-term rates are currently benign, enabling a burst of fiscal stimulus. But let’s not blow it all on state and local governments, green-tech scams, and subsidies for Chinese high-speed rail manufacturers.

Let’s fully abate all federal taxes for individuals for a year or two, payroll taxes as well as income taxes. While we’re at it, let’s also remove the business-income tax on retained earnings for companies below a certain size. And let’s deficit-spend 10% or more of GDP to do these things.

The tax cuts will allow individuals to save money. No, they won’t spend it on current consumption, but they’ll be setting themselves up to a financially-healthy position from which they can expand spending again in a couple of years. If we don’t do that, we’ll be waiting a very long time for private demand to come back, all the while losing sleep over the possibility of higher interest rates on that growing pile of public debt.

And the reason for the small-business tax cut is so that entrepreneurs can finally start creating jobs again. Retained earnings are the most favorable and least expensive growth capital that any small business can hope for. Stop having the government take a huge whack out of them every year, and let us get back to work.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

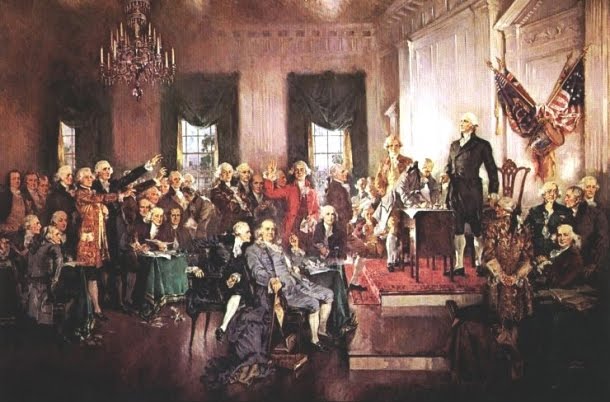

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment