from The American Thinker:

August 30, 2010

Woodrow Wilson and Barack Obama: Lifestyles of the Rich and Progressive

By David Pietrusza

By now, the adjectives have become commonplace for Barack Obama and his administration.

Progressive.

Game-Changing.

Wilsonian.

Yes, similarities do exist between Barack Obama and his Democratic predecessor, Woodrow Wilson. Both are frigidly demeanored but messianic academics. With barely two years of government experience in statewide office, each assumed the presidency and presided over fundamental overhauls of the existing American system.

But here's where one can find another little-noticed but perhaps telling comparison: their work habits.

Barack Obama is already more famous for vacations, golfing, and theater-going than he ought to be. In a period of economic crisis, he is off to Maine and Hawaii and Broadway and Martha's Vineyard. His wife communes with the King of Spain. In time of war, he ducks a Memorial Day ceremony to vacation in America's favorite sun-and-fun vacation spot -- Chicago. He plays basketball. He works out. He golfs and golfs -- and golfs.

The pattern and the perception are set. Aside from Barack Obama's time before the teleprompter, the American public, now out of work, remains unsure of just when this fellow works.

And that brings us back to Mr. Wilson.

It is quite well-known that Woodrow Wilson spent much of the last two years of his tenure stroke-ridden and unable to really work. This is fully understandable and to be sympathized with, not condemned.

But even before his crippling strokes of September and October 1919, President Wilson was no great workhorse.

Again, his health was in play. Even before assuming the White House, he had suffered two lesser strokes. One in 1896 temporarily restricted the use of his right hand. Another in 1906 seriously damaged the vision in his left eye.

Wilson was, as well, diagnosed with arteriosclerosis. Accordingly, Wilson's White House physician, Dr. Cary Grayson, recommended a severely restricted work schedule for his patient. As President, Woodrow Wilson never normally worked more than three or four hours per day. He rarely worked on Sundays. His summer schedule was even more relaxed. He enjoyed cruises upon the Potomac and Chesapeake Bay aboard his presidential yacht. He rode horses. He took long rides in his Pierce-Arrow limousine. After one confusing 70-mile Wilson jaunt through New Hampshire, the Washington Post noted, "STOPS OFTEN TO INQUIRE WAY." When he finally got back, he golfed [i].

Beyond that, Wilson loved to while away his time in light amusements. He thrived upon the theater, particularly vaudeville, and spent every Saturday that he could at B.F. Keith's High-Class Vaudeville Theatre.

"I like the theater ... ," he wrote in 1914, "especially a good vaudeville show when I am seeking perfect relaxation; for a vaudeville show is different from a play. ... if there is a bad act at a vaudeville show you can rest reasonably secure that the next one may not be so bad; but from a bad play there is no escape."

A plaque dedicated at the Keith Theatre in 1931 even marked the frequency of Wilson's attendance (to be fair, the greatest period of that attendance was his stroke-ridden post-presidency). History records him attending the Philadelphia Orchestra at the National Theater or his delighted 1915 presence at stage star Chauncey Olcott's debut in "Shameen Dhu" at Washington's Columbia Theater in January 1915 (Wilson's golf was fogged out that morning) or at Louis Mann's opening night as a German-American in "Friendly Enemies" in 1918.

Like the Obamas, in November 1914, Wilson visited Broadway. But unlike them, for once, he did not attend the theater. Following an afternoon of eighteen holes on Long Island fairways (he shot an 80), Wilson visited his adviser Colonel Edward M. House in the city. Together, they attempted an incognito Broadway stroll. The pair progressed as far as an open-air Salvation Army camp meeting before all hell broke loose. Eventually, Wilson and House took safety from overzealous admirers in the old Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, before Secret Service agents packed the President of the United States off on a passing Fifth Avenue bus and back to Colonel House's 115 East 53rd Street apartment [ii].

Wilson enjoyed motion pictures as well. Following a White House screening of director D. W. Griffith's Birth of a Nation, Wilson allegedly commented that the controversial film was "like writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it is all so terribly true." In any case, Griffith eventually partook of several "fireside chats" with Southern-born Wilson -- although the film pioneer later complained of the president's distinct lack of personal hospitality [iii].

Wilson loved attending baseball games. He was the first president to throw out the first pitch at a World Series. And though he was wise and responsible enough to forgo attendance at Washington's Griffith Stadium during wartime, before the outbreak of hostilities, his attendance at games was fairly common -- at least by president standards. In April 1913 alone, he not only threw out the season's first pitch, but also attended three games of a four-game Senators-Red Sox series.

Vacations? For the first three summers of his presidency, Wilson understandably abandoned Washington for Cornish, New Hampshire's cooler climes. In 1916, he summered at the Jersey shore. Such vacations were lengthy, involving "a month or two"[iv] from his desk -- and they hardly seemed to be working vacations. In August 1915, for example, the Washington Post noted that "a mass of work" awaited Wilson's return from his recent three-week New England stay. Yet a month later, he was headed back to New Hampshire. "He may be away for a week," speculated the Post. "He may stay two or three weeks" [v]. Secretary to the President Joseph Tumulty did not accompany him [vi].

Even when the nation went to war in 1917 and Wilson abandoned such absences, the Post noted he did not forgo his "customary morning golf game" [vii].

Wilson scholar John Milton Cooper also references Wilson's "daily round of golf" and notes that it was when Wilson was departing for the course in May 1915 that he learned of the sinking of the British passenger liner RMS Lusitania by the German U-boat U-20. Wilson canceled his golf. He waited for more news -- it was, however, reported he did not communicate with Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan -- and then went for another limousine ride.

It was, however, after returning from golf one day in March 1915 that the recently widowed Wilson chanced to meet the widow Mrs. Edith Bolling Galt. His frenzied courtship threw his already leisurely work schedule into chaos. Recalled White House Chief Usher Irwin "Ike" Hoover,

The President was simply obsessed. He put aside practically everything, dealing only with the most important matters of state. Requests for appointments were put off with the explanation that he had important business to attend to. Cabinet officers, Senators, officials generally were all treated the same. It had always been difficult to get appointments with him; it was now harder than ever, and important state matters were held in abeyance while he wrote to the lady of his choice. When one realizes that at this time there was a war raging in Europe, not to mention a Presidential campaign approaching, one can imagine how preoccupied he must have been. There was much anxiety among his political friends, who just had to accept the inevitable, but who began to look about for a way to postpone it until after the election, for fear lest the people would not approve [viii].

Yet Wilson survived a Republican resurgence to narrowly gain another term in 1916. The early Wilson years, after all, were years of prosperity. And in comfortable times, it matters not at all whether Ike golfs or LBJ pulls beagles up by their ears. Conversely, when unemployment or inflation stalk the land, it remains of similar low consequence if solemn engineers Herbert Hoover or Jimmy Carter burn the midnight oil to fiddle with the details of a sinking ship of state.

The bottom line: if the American people are at work in 2012, it matters not at all if Barack Obama plays.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[i] Washington Post, 11 July 1913, p. 1. Regarding a Vermont motor jaunt the Post noted; "WILSON LOST IN WOODS . . . RESENTFUL COW HALTS CAR." (Washington Post, 28 June 1915, p. 10). A month later the presidential motorcar was rear-ended in Newport, New Hampshire. (Washington Post, 11 July 1915, p. 1)

[ii] Washington Post, 15 November 1914, p. 8.

[iii] Hart, James (ed.), The Man Who Invented Hollywood: The Autobiography of D. W. Griffith Louisville: Touchstone, 1972, p. 21.

[iv] Washington Post, 25 June 1915, p. 7.

[v] Washington Post, 4 July 1915, p. 2.

[vi] Washington Post, 4 July 1915, p. 2.

[vii] Washington Post, 25 June 1917, p. 7.

[viii] Hoover, Irwin Hood "Ike." 42 Years in the White House. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1934, p. 67.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

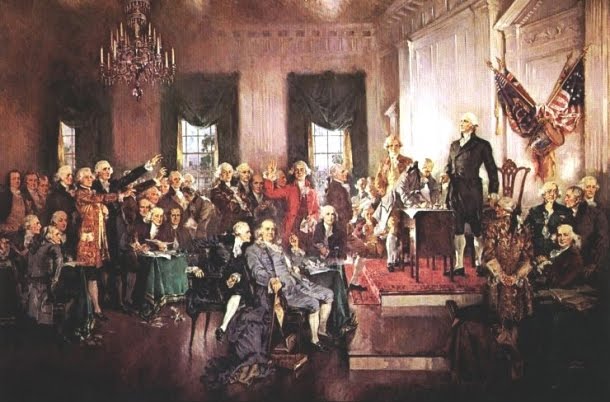

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment