From Investors' Business Daily and The CATO Institute:

The Real Costs Of Social Security

by James A. Dorn

James Dorn is vice president for academic affairs at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., and editor of the Cato Journal.

Added to cato.org on August 24, 2010

This article appeared in Investor's Business Daily on August 20, 2010.

PRINT PAGE CITE THIS Sans Serif Serif Share with your friends:

ShareThisWhen President Obama told the nation last week that Social Security could be put on a sound basis with minor changes, he forgot to tell Americans about the real costs of that system.

Initially, the costs were low: The combined payroll tax rate was only 2% on a wage base of up to $3,000, for a maximum tax of $60 per year. Although the tax was legally split between workers and employers, the incidence of the tax (the effective burden) has always been on workers in terms of lower net wage rates.

Today, workers pay an effective payroll tax of 12.4% for Old Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance on earnings up to $106,800, for a maximum tax of $13,243.20 a year. That tax rate and the cap will continue to increase as the number of retirees grows relative to the working population.

Phony Assets

The real costs of Social Security far exceed the taxes collected: The compulsory pay-as-you-go retirement system has denied people the choice of using those funds for private investment, diminished the culture of responsibility and strengthened the redistributive state. People have become more dependent on government, and the retirement decision has become politicized. Social Security now accounts for 20% of the U.S. budget, with expenditures of $686 billion last year.

Reforms in 1977 and 1983 increased payroll taxes and the retirement age, but made no fundamental changes to the system in terms of empowering workers by allowing them to put part of their Social Security taxes in personal accounts.

The U.S. system has accumulated surpluses, but they have been used to expand the size and scope of government. The so-called trust fund has no real assets, only IOUs that taxpayers must eventually pay.

James Dorn is vice president for academic affairs at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., and editor of the Cato Journal.

More by James A. DornIn contrast, Chile's Social Security Reform Act of 1980 allowed workers to opt out of the defined benefit plan and set up personal accounts. Today Chilean workers are no longer burdened with payroll taxes and no longer dependent on government for their retirement income.

The lack of private property rights in Social Security means that individuals have no secure claim to future benefits and cannot pass them on as part of their estates.

The Supreme Court has ruled that Congress has the power to change promised benefits or other terms of the "social contract" — that is, Congress has the power to break the contract and to renege on past promises.

Needed: $16 Trillion

Indeed, Social Security statements now state: "Congress has made changes to the law in the past and can do so at any time. The law governing benefit amounts may change because, by 2037, the payroll taxes collected will be enough to pay only about 76% of scheduled benefits."

What kind of a contract is that? Would anyone voluntarily sign such an uncertain agreement? Of course not! That's why Social Security is compulsory.

The deal is bound to get worse. This year OASDI will run a deficit of $41 billion, with a smaller deficit in 2011, and surpluses in 2012-14. Beginning in 2015, revenues will be insufficient to pay full benefits, according to the just-released Social Security Trustees' Annual Report to Congress, and the cash-flow deficit will rapidly increase.

From that vantage point, "the crisis is upon our doorstep," said Sen. Judd Gregg of New Hampshire, the ranking Republican on the Senate Banking Committee.

On a 75-year basis, Social Security is bankrupt: Promised benefits far exceed estimated revenues, and if all future benefits beyond this time frame are included, the unfunded liabilities are nearly $16 trillion.

If Medicare is included, the unfunded liabilities soar to more than $100 trillion. That's the amount in today's dollars that is needed to pay off all future benefits over and above taxes collected .

President Obama's debt and deficit commission cannot afford to ignore these massive contingent liabilities and the need for real reform. Doing so will only compound the debt crisis.

The government could temporarily "fix" Social Security by reducing benefits, increasing the retirement age, increasing the payroll tax and raising the tax ceiling.

Those tactics were applied in 1977 and 1983 but have fallen far short of stabilizing the system. That is because the nature of Social Security has remained unchanged — unlike a defined contribution plan (e.g., a 401(k)), a pay-as-you-go plan depends on demographics and on politics.

With an aging population (there will be only 3.3 workers per retiree in 2020 compared with 7.1 workers in 1950), taxes must necessarily increase if promised benefits are to be realized.

But politicians don't win votes by increasing taxes. They would rather increase benefits, and that's exactly what they did in spades from 1967 to '77, when Social Security benefits increased by more than 70%.

Broken Promise

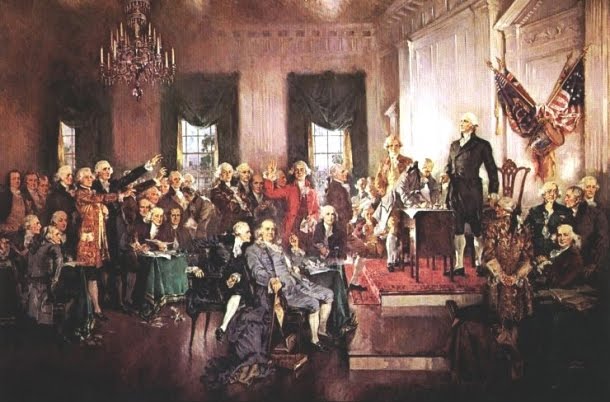

The Framers could never have imagined a welfare state and forced intergenerational redistribution. There have been benefits from the socialized system, but there have also been significant costs — especially the loss of freedom. Individuals are compelled to pay into a system in which nothing is saved or invested, and in which the promise of future benefits can be broken at any time.

Political risk has replaced market risk, and collective responsibility has crowded out individual rectitude.

Chile expanded the market and reduced the scope of government power by removing restrictions on personal accounts and allowing people the choice to stay in the old system or join the new system. That choice is not available in the U.S.; it should be.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment