From Campaign for Liberty:

Antifederalists Vindicated

By Sheldon Richman

View all 40 articles by Sheldon Richman

Published 05/22/10

Printer-friendly version

The latest occasion is this week's 7-2 Supreme Court decision in U.S. v. Comstock et al., upholding a federal statute that permits the civil commitment of a federal prisoner -- beyond his prison sentence -- if he has previously committed a violent sex crime or sexually molested a child, "suffers from a serious mental illness," and thus is "sexually dangerous to others," meaning, "he would have serious difficulty in refraining from sexually violent conduct or child molestation if released."

Note well: Someone in the federal prison system can be held indefinitely after he's served his sentence. For the purposes of this article, I leave aside some extremely important issues, including whether any government should have the power to incarcerate (even if in a "hospital") someone because a psychiatrist says he has a "mental illness" and may "have serious difficulty in refraining" from sexually criminal activity in the future. This is a far cry from the traditional criminal law. Readers of The Freeman will know that these subjects have been thoroughly examined over the years by Thomas Szasz, who maintains that the diagnosis "mental illness" is a metaphorical, pseudoscientific way of dealing with undesirable behavior; that civil commitment, or involuntary mental hospitalization, is a "crime against humanity"; and that people should be punished with only after they have been proved to have committed a crime and only for that crime. (He has also relentlessly opposed the insanity defense and verdict.)

The statute in question surely violates the principles of liberty and justice. But the question is whether it violates the Constitution.

The chief matter before the Court was whether the law satisfies the Constitution's Necessary and Proper Clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 18), which authorizes Congress "To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof."

Writing for the majority, Justice Stephen Breyer said that the commitment statute falls well within the clause as it has been interpreted from the earliest days of the Republic. Quoting terms from the early landmark case McCulloch v. Maryland, Breyer wrote, "[T]he Necessary and Proper Clause makes clear that the Constitution's grants of specific federal legislative authority are accompanied by broad power to enact laws that are ‘convenient, or useful' or ‘conducive' to the authority's ‘beneficial exercise.'"

He noted that past Courts have allowed Congress great discretion in determining if a means is necessary (not "absolutely necessary") and proper for achieving a constitutional end.

Indeed, Breyer wrote, the chain between a statute and the constitutional powers that it is deemed to executing may have several links. "Congress has the implied power to criminalize any conduct that might interfere with the exercise of an enumerated power, and also the additional power to imprison people who violate those (inferentially authorized) laws, and the additional power to provide for the safe and reasonable management of those prisons, and the additional power to regulate the prisoners' behavior even after their release."

Thomas Dissent

In his dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas (writing on behalf of Justice Antonin Scalia also) said that Breyer has misread the Clause and long precedent. For Thomas, convicting someone of a federal crime under a law that satisfies the Necessary and Proper Clause gives the government no additional authority to civilly commit after sentence is served. In other words, whatever enumerated power ultimately justified the person's initial imprisonment, it cannot convey legitimacy to postsentence detention. The chain is too long for Thomas.

"The Constitution does not vest in Congress the authority to protect society from every bad act that might befall it." He added, "[I]f followed to its logical extreme, [Breyer's approach] would result in an unwarranted expansion of federal power.

Is It a Draw?

Both sides appear to make sound constitutional arguments. Although I of course prefer Thomas's conclusion -- commitment is an outrageous violation of individual liberty -- that is irrelevant. The point is, people can reach opposing conclusions through the text of the Constitution and past decisions. Remember: The Court's four conservative "strict constructionists" split down the middle.

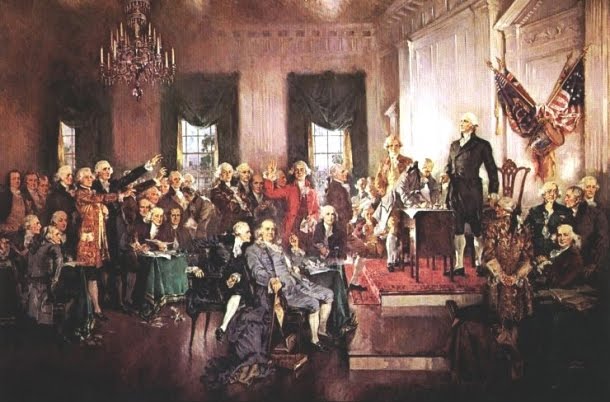

That's where the Antifederalists come in. The Necessary and Proper Clause was one of several clauses they most objected to when the text of the Constitution was released to the public in 1787. Combined with other vaguely "enumerated powers," they found the clause threatening to liberty and a portent of big government.

As the Antifederalist "Brutus" wrote, because of the Necessary and Proper Clause and the Supremacy Clause, "This government is to possess absolute and uncontroulable power, legislative, executive and judicial, with respect to every object to which it extends."

And "Federal Farmer," wrote, "To have any proper idea of their [the laws'] extent, we must carefully examine the legislative, executive and judicial powers proposed to be lodged in the general government, and consider them in connection with [the Necessary and Proper Clause]. . ..[I]it is almost impossible to have a just conception of these powers, or of the extent and number of the laws which may be deemed necessary and proper to carry them into effect. . .."

In other words, the constitutional text is not nearly as crisply clear as people would like to think, despite the temptation to read one's own values into it. Thus it makes a shallow foundation for liberty. We can rely on no text to interpret and enforce itself, so we must make the case for liberty and justice directly.

Their contemporaries should have listened to the Antifederalists' warnings when they had the chance.

Copyright © 2010 Foundation for Economic Education

No comments:

Post a Comment