From The American enterprise Institute:

SPEECHES & TESTIMONY The First Post-American President and American Sovereignty By John R. Bolton

Heritage Foundation

(May 18, 2010) John R. Bolton, senior fellow at AEI, presented to the Heritage Foundation at an event in Chicago. His remarks follow.

I'm delighted to be here today and very much look forward to this. I want to talk a little bit about President Obama and then I'd be delighted to answer your questions on really any subject that's on your mind. And I'd like to start out with what I think is a very, very important point, and that is that on January the 20th of last year, when he took the oath of office, Barack Obama was not qualified to be president. Today, 15 months later, he is still not qualified to be president. I could spend a lot of time on domestic policy but I'm going to skip that to concentrate on what I think the graver threat is that he poses, although he poses so many threats that it's hard to prioritize them.

Americans normally think of their president as our chief advocate in the world, that this is the leader who is going to defend us against challenges and adversity that we face. I don't think Obama sees himself that way and I don't think his administration does either.But I think on the national security front, which is obviously should be the president's first responsibility, we're only beginning to see the negative consequences of what I will loosely term "his leadership of our foreign policy." And I think there are a couple of characteristics about Obama that it's important to understand. The first is he doesn't really care about national security. It's not what gets him up in the morning. What gets him up in the morning is restructuring our health care system, restructuring our financial system, restructuring our energy system, restructuring--well, you get the point. Unlike John Kennedy and unlike the line of presidents since Franklin Roosevelt, who cared primarily about threats to our national security, he is just not interested. He addresses them when he has to, when it's unavoidable, but that's not where his attention is focused, number one.

Number two, he doesn't see challenges and risks for the United States in the rest of the world. During the campaign, he told us that Iran was just a tiny country and therefore, implicitly, nothing to worry about. He doesn't want to talk about the global war on terrorism. His attorney general has trouble mouthing the words Islamic fundamentalism. I think the president believes, in some sense, not that he will ever say it, that American decline is inevitable, natural, and probably, on balance, a pretty good thing. That makes him unique among American presidents.

Now, normally, when you have a president who doesn't care about foreign policy and who doesn't see the rest of the world as terribly threatening or challenging to the United States, you would expect a kind of isolationist policy. But that's not the direction that Obama has taken. It's quite the contrary. He looks at the world through a very multilateralist prism. Not since Woodrow Wilson really had we had a president whose focus is so multilateral. And in fact, if you read some of the things that President Obama has said particularly at the United Nations last September, it's very hard to distinguish his rhetoric from Wilson's rhetoric at the end of World War I.

So you put all this together and to me, it explains why President Obama is what I've called our first post-American president. Post-American, a phrase I choose carefully. I didn't say "un-American." I didn't say "anti-American." I said "post-American" because he is beyond all that patriotism stuff. He has moved beyond. He's a citizen of the world and he's a citizen of the world in large part because he doesn't believe as we do in American exceptionalism.

Now, this is a doctrine that you could talk about almost endlessly, but it started really with Gov. John Winthrop of the Plymouth Bay Colony. When paraphrasing scripture, he said, "We shall be seen as a city on a hill." Ronald Reagan, of course, amended that to make us "a shining city on a hill." Some people take offense at American exceptionalism. They say it's the typical American sort of looking down at the rest of the world. I'd just remind everybody that the first person to comment on American exceptionalism was French, Alexis de Tocqueville, who, in Democracy in America, said, "The position of the Americans is therefore quite exceptional, and it may be believed that no democratic people will ever be placed in a similar one." And many others have commented on it down the years as well.

The president was asked, on his first trip to Europe as president, if he believed in American exceptionalism. And in a classic Obama answer, he said, and I quote, "Yes, I believe in American exceptionalism, just as the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believed in Greek exceptionalism." So in the first third of the sentence, he is able to put on record something that allows him to say, when people like me say he doesn't believe in it, he can say, "Well, of course, I do. I just said it." But read the other two-thirds of the sentence. There are 192 members of the United Nations. He only named three. He could have gone on, just as the Ecuadorians believe in Ecuadorian exceptionalism, just as the Burkina Fasians believe in Burkina Fasian exceptionalism, just as the Papua New Guineans believe in Papua New Guinean exceptionalism. Obviously, if everybody is exceptional, nobody is, and I think that's really what he thinks. And this is an assessment that others, not on our side of the spectrum, have perceived as well.

Evan Thomas, a senior editor of the soon-to-be bankrupt Newsweek Magazine--certainly, it's a periodical. Only half of its name is right--commented on Obama's speech at the 65th anniversary of the D-Day landing and he, Thomas, was comparing it to Ronald Reagan's famous speech on the 40th anniversary. This is what Evan Thomas said, "Reagan was all about America. Obama is, 'We are above that now. We're not just parochial. We're not just chauvinistic. We're not just provincial. We stand for something.' I mean in a way, Obama is standing above the country, above the world. He is sort of God. He is going to bring all the different sides together."

Now, other than the reference to God, which is a little bit over the top even for the mainstream media, I think that's not an inaccurate description of how Obama sees himself. He is not the first American politician to hold that view. He is certainly the first to be elected president. But if you think back to what then Vice President Bush said in 1988 about Michael Dukakis, his opponent for the presidency that year, Bush said about Dukakis, "He sees America as another pleasant country on the UN roll call, somewhere between Albania and Zimbabwe." And that's much the same way that Obama sees it. It's the U.S. has its interests, but so does everybody else.

Now, Americans normally think of their president as our chief advocate in the world, that this is the leader who is going to defend us against challenges and adversity that we face. I don't think Obama sees himself that way and I don't think his administration does either. We just heard over the weekend, for example, that the Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights, in the annual human rights discussion with China--that's always a pleasant encounter--that this Assistant Secretary of State volunteered at a press conference that he had raised Arizona's new immigration law as an example of problems that the United States still had. He said, "We raised it early and often." This is the kind of moral equivalence that says, "Well, China has a large Gulag. It deals with illegal immigrants by killing them. It doesn't have democratic procedures. So they've got their problems and we've got Arizona." This Assistant Secretary of State should be fired for what he said. I predict he will be promoted in due course. And this is really I think a very important point in understanding Obama, in understanding the State Department.

While we're on the subject, you hear something like this, it strikes you as outrageous. But even if it's corrected, that doesn't mean that you've solved the problem. This is not some extraordinary aberrational behavior in the Obama administration. This is par for the course. This is happening at every level in national security affairs over and over again in many ways that we're just simply not familiar with. And it is the kind of behavior that has a corrosive impact on our overall national security. And let me just take a couple of examples.

Number one, I think that the post-American approach that the president brings to his job and the many appointees in subordinate positions who not only share that view but probably take it a lot further is going to have consequences for us in terms of our sovereign interest in ways that we can't calculate. Now, overseas, they're not so reluctant to talk about some of the objectives. They're more explicit than they are in the United States. But that same social democratic mindset that the president has is widely reflected, for example, in Europe. And so I thought it was very instructive in November of last year at the inauguration of the first president of Europe--you're all familiar with him, Herman Van Rompuy; that name resonates with all of you, I know--he is now president of the European Union and in his inaugural address, which was just before Copenhagen, he said, and I quote, "2009 is the first year of global governance with the establishment of the G20 in the middle of the financial crisis. The Climate Conference in Copenhagen is another step toward the global management of our planet."

Now, the Europeans are very expert at surrendering their sovereignty to Brussels. They've been at it for some time. Actually, I should say it's the European elites that are very good at that. The population of European countries, whenever they get a chance to express themselves through referenda, typically reject a lot of these ideas, but the political class is determined to cede more and more sovereignty to Brussels. Now, we don't have a European Union, thank goodness, and we're not eligible to join, but I think this tendency to look toward what sounds benign, in a sense, "the global management of our planet" is very much in the president's agenda, and I'd tell you the real risk that Copenhagen could have brought us is not misperceptions necessarily about climate change, but the extraordinary concentration of power, regulatory power, taxing power, and authority generally over the environment that had the countries reached agreement on the draft declaration would have brought us.

The fact is that whether we're suffering from global warming or global cooling or whether the temperature of the planet is constant, the people who advocated the solutions in Copenhagen were people who advocated those solutions before global warming became the flavor of the day and they'll advocate it, if tomorrow, the scientists tell us that we're suffering from global cooling. It is a pressure toward ceding national authority to international organizations and international conventions that leaves all of us less in control of our own lives.

Now, for Americans, sovereignty is not an abstract concept. It's not some monarch far away from us. We understand very well that under our constitution, sovereignty is vested in us, in America. It's not the government that's sovereign. It's the people who are sovereign. So when you hear--when you hear people say, "Well, you know, problems today are really global in nature and therefore, you need global solutions and what we need to do is to share sovereignty or to pool sovereignty," what they are saying indirectly to Americans is, "You have too much control over your own government and you need to give some of it up to Germans and Chinese and South Africans and all the other members of the United Nations."

I think since most Americans think we don't have enough control over our own government, the last thing we want to do is give what we have up in whole or in part. And I think it's important, as you look at a range of issues that are being discussed, some in Congress, some in international organizations covering a huge diversity of subjects, from the idea of international fees and taxes for banks that would fund international regulatory activities to the Law of the Sea Treaty, which the administration is trying yet again to get through Congress that would fund an international authority from revenues, royalties of deep-sea mining, to any of a variety of other things, including issues like gun control, the death penalty, family issues, that the tendency to put more and more of these issues into international negotiations is a tendency that we should resist because it is ultimately destructive of our liberties. If we can't control the flow of these decisions through our elected representatives, much like the people of Europe who find more and more of their laws being negotiated in Brussels in completely opaque circumstances and then brought back to their parliaments, where the only role their parliament has is to rubberstamp what's already been negotiated, as we get sucked into that kind of process, we are going to find it more and more difficult to preserve self-government here.

Now, this doesn't happen all at once. In fact, one of the difficulties in explaining it is that too often, these issues take place with all of the speed and with all the visibility of a coral reef growing. But that's why you have to look for the implications of sovereignty in a lot of different ramifications. And why I think it's very important as we come up to a significant election this fall and then again in 2012, that we hear more and more from our candidates. In fact, as citizens, that we demand to hear from our candidates what their views are on this subject.

When we have a nominee for the Supreme Court, I think it's very important for senators to ask in the confirmation hearing what place they think international law has in determining the interpretation of our constitution. I personally think it has no place in interpreting our constitution. I'd like to hear more politicians say unequivocally that in terms of life on earth, there is no higher authority for Americans than the U.S. constitution.

This is not something that our friends in Europe like to hear, but I think it's very important for us to have an understanding of the implications of this sort of activity because otherwise, it will creep up on us. It is creeping up on us and we will establish precedents that will be difficult to undo and that will come back to haunt us in the future.

Now, let me just turn to a more immediate concern in closing here, before I answer your questions because it's something that we're seeing unfold in front of us, sadly, even as we meet today, and that is the increasing likelihood that the government of Iran is going to have nuclear weapons in the very near future. We have, both during the Bush and the Obama administration, pursued a policy based on a fundamentally incorrect assumption, that assumption being that Iran could be negotiated out of its nuclear weapons aspiration. In fact, Iran has been pursuing nuclear weapons for 20 years. They've made enormous progress under the cover of negotiations during the past seven years. They've overcome all of the scientific and technological obstacles that stand in the way of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles to deliver the weapons. They're very close to the point where they can essentially weaponize at a moment of their choosing.

The administration came into office saying that they would give Iran a choice, carrots and sticks, incentives and disincentives, as if they had just discovered something. This was exactly what our European friends were offering to Iran for the last six years of the Bush administration, and the Iranian response was remarkably consistent. "Thank you for the carrots. They're not enough. Forget the sticks. We're going to develop our uranium enrichment capability."

So, imagine the surprise of the Obama administration when, after a year and several months, the Iranian response was exactly what it had been for the past six years. Can you imagine that the Iranians could do that to our new president? And then the administration said, "Well, we've decided that it's now time to turn to the sticks part of the thing. We're going to pass a strong sanctions resolution in the UN Security Council," sort of ignoring the fact that the Security Council had already passed three sanctions resolutions, which had not slowed Iran down in the slightest. And just in the middle of the triumphal procession toward this fourth meaningless Security Council sanctions resolution, our NATO ally Turkey and our ally Brazil in this hemisphere went to Tehran and negotiated a deal with Mahmoud Ahmadinejad that essentially turned the whole sanctions affair into a charade because this will buy time, more time for Iran to proceed to create its nuclear weapons capability.

Now, just before we convened here today, Secretary Clinton said in Washington that this afternoon, we will be introducing our sanctions resolution in the Security Council. Anyway that the five permanent members in Germany have agreed on it and we're going to proceed regardless of what happened in Tehran. This is sort of the ultimate humiliation because wait until about 24 or 48 hours from now, when Russia and China, hearing the report from Brazil and Turkey, who are both nonpermanent members of the Security Council, reverse their support for this draft sanctions resolution.

The fact is that the Obama administration's policy has failed here. It's failed with respect to North Korea's nuclear weapons program. It's failing in the Middle East. It's failing in every material issue that we've got around the world because it's based on the misperception that America's role in the world had been diminished by our unwillingness to negotiate with our adversaries. The fact is that negotiation, like anything else in human life, has costs and benefits. And when you're dealing with proliferators, negotiation, which is protracted normally, almost always benefits the proliferators. That's what Iran understood quite well, going on seven years now. That's the policy that they have exploited and so we're at the point where Iran is very close to getting that nuclear weapon that it's long sought.

I'm afraid the real Obama administration's strategy is to accept an Iran with nuclear weapons. I think that's a disaster waiting to happen. The administration thinks Iran can be contained and deterred in the same way we contained and deterred the Soviet Union. I think that's a miscalculation. The perceptions of the leadership in Iran are very different than the leadership in Moscow during the Cold War. But even if I'm wrong on that, it doesn't stop with Iran. If Iran gets nuclear weapons in short order, Saudi Arabia will have them, Egypt will have them, Turkey will have them, others.

So in a brief period of time, five to ten years, you could have half a dozen countries in the Middle East with nuclear weapons. And if you didn't like the tension and uncertainty of the bipolar nuclear standoff during the Cold War, imagine the uncertainty created by a multilateral nuclear Middle East. I think now, we're down to two options. One is we accept Iran with nuclear weapons or two, somebody uses preemptive military force against the Iranian nuclear weapons program.

You can bet it won't be the Obama administration, so that leaves the decision resting on Israel, which sees an Iran with nuclear weapons as an existential threat. Faced with that kind of threat before, Israel has not hesitated to act, destroying Saddam Hussain's Osirak reactor in 1981, and destroying a North Korean reactor in Syria in September of 2007. What is the Obama administration reaction to the possibility that Israel might strike? Threatening Israel to withhold the re-supply of planes and weapons lost in any such strike, thus, putting Israel very much at risk of retaliation by Hezbollah and Hamas after the strike takes place. This is an administration that cares more about stopping Israel than it does about stopping Iran, and that is a fundamental mistake, not for Israel, for the United States because our national security will be extraordinarily negatively affected once Iran gets nuclear weapons.

So I have only this to say in conclusion. Although it's been a bad 16 months or so since the president took office, we've got two years and eight months more of bad news. The fact is no matter what happens in the congressional elections this fall, the president has the main constitutional authority in foreign policy and unless we can spark a broader public debate than we have on these national security issues, we are going to see a decline in American power and influence around the world that even a new president in 2012 will have a substantial difficulty in overcoming.

We will be in a period of vulnerability because of military budget decisions that take time to overcome that our adversaries well understand and will take advantage of. That's why I think it's critically important as citizens that we don't allow ourselves to be diverted into speaking only about domestic issues, as important as they are. We have to keep national security at the top of the agenda. That's where it should be for our president. It's not so, it's up to us as citizens to put it there. Thank you very much.

John R. Bolton is a senior fellow at AEI.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

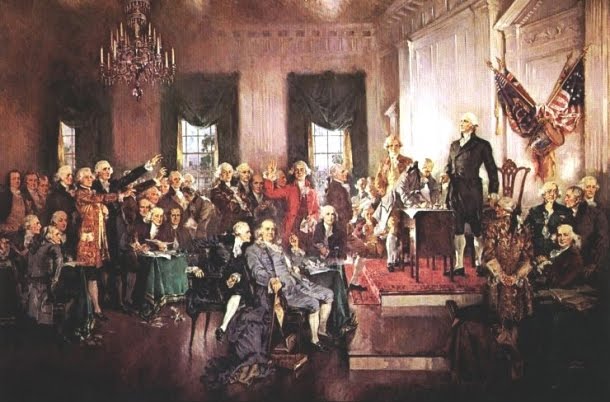

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

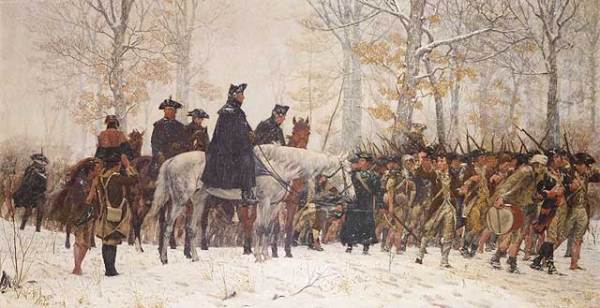

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment