From The Heritage Foundation:

The OAS Firearms Convention Is Incompatible with American LibertiesPublished on May 19, 2010 by Theodore Bromund , Ray Walser, Ph.D. and David Kopel Abstract: President Barack Obama has called on the Senate to ratify CIFTA, the Inter-American Convention Against the Illicit Manufacture of and Trafficking in Firearms, but the convention poses serious prudential risks to liberties guaranteed by the First and Second Amendments. The convention appears to be an end run around domestic obstacles to gun control. Furthermore, ratification of the convention would undermine U.S. sovereignty by legally binding it to fulfill obligations that some current signatories already disregard. The U.S. would be best served by continuing existing programs, cooperating with other countries on a bilateral basis, and making and enforcing its own laws to combat the traffic in illicit arms.

President Barack Obama has called on the Senate to ratify the Inter-American Convention Against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives, and Other Related Materials.[1] President Bill Clinton signed the convention in 1997, but neither he nor President George W. Bush sent it to the Senate for advice and consent for ratification. The convention, commonly known by its Spanish acronym CIFTA,[2] was negotiated under the auspices of the Organization of American States (OAS).

The convention poses serious prudential risks to liberties associated with the First and Second Amendments. Specifically, it seeks to criminalize a wide range of gun-related activities that are now legal in all states, and it would clash with the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. It would also entitle foreign governments to legal assistance from U.S. authorities when pursuing extradition requests, including requests to arrest individuals exercising their First Amendment rights. These are serious prudential risks. Finally, it would create a chilling climate for the freedom of speech of foreign nationals both in the United States and in the Western Hemisphere as a whole.

More broadly, the convention poses risks to American sovereignty. Because the convention has no enforcement mechanism, by ratifying it, the U.S. would impose one-sided obligations upon itself, thereby illegitimately constraining American governing institutions. In some cases, these obligations would be constitutionally unacceptable and could not be enforced. This would place the U.S. in the position of ratifying a treaty that it cannot entirely fulfill, creating an opening for critics to condemn the U.S. for failing to live up to its international obligations.

The conflict between the U.S.’s treaty obligations and the Constitution would also be useful to domestic advocates who argue that the Constitution is a barrier to U.S. compliance with “international norms.” Thus, the convention fits neatly into a broader transnationalist strategy to reduce the ability of the U.S. to govern itself through laws and institutions of its own making. By backing the convention, its advocates also advance the idea that the U.S. should act at the suggestion and under the guidance of other states and ultimately of the “international community.”

The defects in the convention are serious and pose prudential risks that cannot be remedied without a substantial number of U.S. reservations to the convention. It is particularly troubling that Harold Koh, a key Administration appointee, offered an unqualified endorsement of the convention before taking office and expressed doubt about the legal validity of reservations. While his criticism of the legality of reservations is baseless, the number and extent of the necessary reservations would be substantial and incompatible with the core of the convention. The U.S. can therefore neither properly ratify the convention with reservations nor safely ratify it without reservations.

Furthermore, the convention is fundamentally an arms control treaty but is not being treated with the seriousness that should attend arms control agreements. This is dangerous, and the Senate should be wary of these problems if it considers the convention.

The Convention’s Purposes, Requirements, and Problems

The convention’s declared purposes are twofold:

To “prevent, combat, and eradicate the illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms, ammunition, explosives, and other related materials.”

To “promote and facilitate cooperation and exchange of information and experience among States Parties to prevent, combat, and eradicate the illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms, ammunition, explosives, and other related materials.”[3]

To those ends, the convention requires signatories to adopt legislative or other measures to criminalize a broad range of activities defined by the convention. The signatories must apply a series of requirements to the manufacture, assembly, police seizure, and disposal of firearms and related materials; a further series of requirements to the international trade of these items; and additional requirements intended to promote cooperation among the signatories.

The convention’s requirements are problematic for three reasons.

First, they mandate the creation of a domestic license system, which would have serious implications for Second Amendment rights, domestic commerce and international trade, and privacy rights. There is reason to believe this license system is intended as an end run around domestic obstacles. Its constitutionality is unclear, and its broad reach is certainly imprudent.

Second, the convention seeks to criminalize speech and creates wide-ranging grounds for extradition. Its supporters seek to use the convention to restrict rights under the First Amendment.

Third, the facts do not support claims that the convention would address the security challenges on the U.S.–Mexican border. Indeed, because the convention has been and will continue to be ineffective, it would become a one-sided and illegitimate constraint on American sovereignty.

Mandated Creation of a Domestic License System. The convention’s preamble states that it does not apply to “firearms ownership, possession, or trade of a wholly domestic character.”[4] This provision is obviously subject to interpretation of what is “wholly domestic.” As President Clinton implied upon signing the convention on November 14, 1997—“in [this] era…our borders are all more open to the flow of legitimate commerce”—the concept of globalization is often held to imply that nothing is a wholly domestic concern.[5] Thus, the convention’s preamble offers no meaningful protection to domestic firearms ownership or trade.

Even more important, the convention’s exclusion of wholly domestic activities applies only to “ownership, possession, or trade.” It does not cover manufacturing or assembly. In Article 1, “Definitions,” the convention prohibits the unlicensed “manufacture or assembly of firearms, ammunition, explosives, and other related materials.”[6] Manufacturing and assembly are obviously domestic activities. The “related materials” are in turn defined as “any component, part, or replacement part of a firearm, or an accessory which can be attached to a firearm.”[7] Thus, the convention very broadly defines the “manufacturing or assembly” that requires “a license from a competent governmental authority.”[8]

The creation of such a licensing system is not optional: It is the core of the treaty. Article 4, “Legislative Measures,” clearly states that “States Parties that have not yet done so shall adopt the necessary legislative or other measures to establish as criminal offenses under their domestic law the illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms, ammunition, explosives, and other related materials.”[9] The convention would therefore require either all of the states or the federal government to enact legislation to require a license for all manufacturing or assembly as defined by the convention and to define unlicensed manufacturing or assembly as a crime.

The convention’s inclusion of “related materials” would require a license for the manufacture of all firearm spare parts and accessories that attach to firearms, such as scopes, ammunition magazines, sights, recoil pads, bipods, and slings. The manufacture of items such as screws or springs that are sold to firearms manufacturers or private gun owners but that also have many other uses entirely unrelated to the firearms industry would also be subject to the licensing requirement.

These requirements are broad, but the convention extends even further because it covers “assembly” as well as “manufacturing.” Federal law already requires a license to manufacture firearms, but it defines a “firearm” as the receiver of the gun.[10] However, under the convention, attaching any accessory to a firearm—even a sling for a hunting rifle—would require a license, as would any repair of a firearm by a private individual or home manufacture of ammunition (“reloading”). All of these activities are legal and practiced in all states. Ultimately, to comply with the convention’s “manufacturing and assembly” clause, almost all gun owners would need to be licensed as manufacturers, assemblers, or both.

Under federal law, the premises of firearms and ammunition manufacturers may be inspected without notice once per year by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). In cases involving a criminal investigation, unlimited inspections without notice are legal.[11] The licensing system and the criminal penalties required by the convention would substantially expand the intrusive power of the federal government and apply this power directly to the homes of millions of Americans.

Burden on Legitimate Domestic Commerce. On the domestic front, Article 7, “Confiscation or Forfeiture,” would prohibit police authorities from selling confiscated firearms to licensed firearms dealers, a common and regulated U.S. practice.[12] Even more seriously, Article 8, “Security Measures,” requires states parties, in “an effort to eliminate loss or diversion,” to “adopt the necessary measures to ensure the security of firearms, ammunition, explosives, and other related materials imported into, exported from, or in transit through their respective territories.”[13] It is unclear what constitutes “necessary measures,” how they are to “ensure” security, or whether guns owned domestically would be considered to be “in transit.”

However, because the purpose of Article 8 is to “eliminate loss or diversion” from licit to illicit owners within a nation’s borders, the convention could be held to require the U.S. to “ensure the security” of all privately held firearms and related materials. Such security measures could include a regulation mandating that legal owners of firearms purchase federally approved safes in which to store them. A requirement of this nature might make firearms possession prohibitively expensive. At a minimum, the convention requires the U.S. to assume federal responsibility for ensuring the security of all legally manufactured firearms, ammunition, and related materials being exported, arriving as imports, or in transit across the U.S. Even this requirement would be burdensome and intrusive, requiring a vast expansion of federal authority and bureaucracy.

Free Trade Concerns. The convention has broad implications for international trade. All countries require official authorization for the commercial import or export of firearms, but authorization is not required in most cases for the import or export of items such as slings, springs, or screws. Yet the convention requires a license for commercial or noncommercial cross-border transfer of the same set of items for which a manufacturing or assembly license is required. It defines illegal trafficking as “the import, export, acquisition, sale, delivery, movement, or transfer of firearms, ammunition, explosives, and other related materials from or across the territory of one State Party to that of another State Party, if any one of the States Parties concerned does not authorize it.”[14]

This phrasing, like the phrasing of Article 9, “Export, Import, and Transit Licenses or Authorizations,” implies that all relevant states parties must outlaw all trade in this broad range of items, except when the trade is explicitly authorized. This requirement would impose serious burdens on currently legal trade far beyond the firearms industry. It also raises both Second Amendment and free trade concerns.

OAS Model Legislation Establishes a Gun and Ammunition Registry. The OAS has produced model legislation for use by states that have ratified the convention. Of course, if the Senate ratified the convention, the U.S. would not be required to use this model legislation in drafting implementing legislation. However, the model legislation gives substance to the convention’s requirements and sheds light on the agenda of the OAS and the convention’s supporters.

Furthermore, the model legislation establishes an OAS-approved interpretation of the convention’s requirements, and the convention states in its preamble that states parties “will apply their respective laws and regulations in a manner consistent with this Convention.”[15] If it considers the convention, the Senate should consider adopting a reservation stating that neither the preamble nor the model legislation has any bearing on the U.S.’s legal obligations arising from the convention and that the U.S. will remain the sole and exclusive interpreter of its obligations.

The model legislation requires not only that all firearms be marked, but also that “[e]very person who manufactures ammunition shall ensure that each cartridge [i.e., each individual round of ammunition] is marked at the time of manufacture.”[16] This would directly affect Americans who manufacture ammunition at home. The requirement that each cartridge be marked with a unique batch or lot number would also require commercial manufacturers to retool their assembly lines at substantial cost.

The model legislation further requires that “[i]nformation on manufactured, imported, and confiscated or forfeited firearms and ammunition shall be kept and maintained in a registry” and that this information must include “[t]he name and location of the owner of a firearm and/or ammunition and ammunition boxes and each subsequent owner thereof, when possible.”[17]

In short, the model legislation requires creation not only of a national gun registry, but also of a national ammunition registration down to the level of individual rounds of ammunition. Every time a hunter bought a box of ammunition, his or her name would be entered into the registry and individually and distinctly identified with every round of ammunition in the box. The model legislation also requires the collecting of information on “destroyed firearms and ammunition,” which implies that legitimate users of ammunition would be required to collect spent shells and display them to federal authority to prove they were legally expended in order to have them removed from the registry.[18]

Apart from the Second Amendment implications, this registration system would become a bureaucratic nightmare, quickly mushrooming into billions of entries. This would incentivize creation of a large black market in unlicensed firearms and ammunition. The model legislation’s “when possible” clause would have no practical effect, because supporters of the convention could argue that the U.S. is capable of doing everything the model legislation requires.

Broad Implications for Privacy. The model legislation also requires that information be maintained in the registry for 30 years. This 30-year requirement is an elaboration and expansion of Article 11, “Recordkeeping,” which requires that “States Parties shall assure the maintenance for a reasonable time of the information necessary to trace and identify illicitly manufactured and illicitly trafficked firearms.”[19] However, this information will not be held just by U.S. authorities. Article 13, “Exchange of Information,” requires that the information be shared with all states parties of the convention.[20]

These states, in turn, are not strictly bound by the terms of Article 12, “Confidentiality,” to keep private any information they receive.[21] Thus, the information collected about the gun and ammunition ownership by individuals in the U.S. would be accessible to fiercely anti-American members of the OAS, such as Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez, whose only obligation under the convention would be to notify the U.S. before making public use of it. This would be a further intrusion into the privacy of U.S. citizens that goes far beyond any measures necessary to achieve the convention’s purported objective.

Furthermore, the requirement that all states parties obtain and hold this information also implies that the purpose of the convention and the model legislation is to create a national firearms and ammunition registry. This would appear to clash with the Firearms Owners’ Protection Act (FOPA) of 1986, which forbids national gun registration.[22] It is unclear how the courts would resolve this apparent clash. However, to the extent that the convention and its implementing legislation conflict with FOPA, the implementing legislation, as the latter enactment, would prevail.

More broadly, the model legislation’s requirement that the information for its national registry be maintained for 30 years serves no legitimate purpose and is, in the convention’s terms, not “reasonable.” The purported purpose of the convention is to control cross-border sales and transfers, not to collect and maintain ownership information across the entire United States for more than a generation.

An End Run Around Domestic Obstacles. The expansive scope of the convention and the model legislation suggests that it is simply a disguised gun control measure. The statements of the convention’s supporters substantiate this concern.

Before taking office as the State Department’s Legal Adviser, Harold Koh wrote that “the only meaningful mechanism to regulate illicit transfers is stronger domestic regulation,” that “[s]upply-side control measures within the United States” are essential, and that the U.S. should “establish a national firearms control system and a register of manufacturers, traders, importers, and exporters.” This is precisely what the convention seeks to accomplish. Koh stated that he felt called upon to “do more” on the “global regulation of small arms” and described even referring to Second Amendment rights as “needlessly provocative.”[23]

For its part, the Center for American Progress openly blames “permissive gun ownership laws” in the United States for causing a substantial part of Mexico’s problems with drug-related gang violence.[24] Given such statements, supporters of Second Amendment rights have cause to be concerned about the convention’s actual purpose and the motives of its advocates.

Furthermore, under President Clinton, the U.S. adjusted its regulatory structure to comply with portions of the convention even though the Senate had not yet considered it.[25] Thus, the convention is already playing the transnational role that its supporters advocate.

Unclear Constitutionality. During her confirmation hearing, Ambassador Carmen Lomellin, Permanent U.S. Representative to the Organization of American States, responded to a question about the convention’s licensing requirements and its incompatibility with the Second Amendment by committing herself to protecting Second Amendment rights from international restrictions.[26] The Administration is therefore on record as recognizing that, in any conflict between the convention and the Second Amendment, the convention must give way.

While it might thus be argued that the Administration accepts that the Second Amendment would restrict the applicability of the convention in the United States, the convention does not ban any type of gun or restrict the use of firearms for self-defense, putting it outside the core of District of Columbia v. Heller. In Heller, the Supreme Court stated that “laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms” were presumptively constitutional.[27] On those grounds, the convention’s licensing requirement for noncommercial manufacture or assembly would appear to be in a constitutional gray zone.

On the other hand, because Heller does not deal explicitly with the noncommercial manufacture and assembly that the convention seeks to regulate, there is no assurance that the Supreme Court would regard this central part of the convention as acceptable. In short, neither supporters nor critics of the convention can point to a controlling legal authority that clearly and unambiguously sustains any argument about the convention’s effect on Second Amendment rights in the United States.

Excessively Broad Reach. While the Second Amendment is the controlling U.S. authority on firearm ownership and use, a broader perspective is also important. The Founding Fathers believed that the right to keep and bear arms was important to the defense of liberty, which was why they added the Second Amendment to the Constitution. As James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 46:

Besides the advantage of being armed, which the Americans possess over the people of almost every other nation, the existence of subordinate governments, to which the people are attached, and by which the militia officers are appointed, forms a barrier against the enterprises of ambition, more insurmountable than any which a simple government of any form can admit of. Notwithstanding the military establishments in the several kingdoms of Europe, which are carried as far as the public resources will bear, the governments are afraid to trust the people with arms. And it is not certain, that with this aid alone they would not be able to shake off their yokes.[28]

Madison’s point that Americans were already armed raises a final point—one of prudence. Ratification of the convention and adoption of implementing legislation in accordance with its requirements would criminalize many activities that are currently lawful but which bear no relation to illegal arms trafficking into Mexico or anywhere else.

Criminalizing the lawful activities of millions of American citizens through the licensing system required by the convention would bring the law into contempt, create distrust of the treaty-making process, and continue the unprecedented expansion of federal criminal law that has rendered it all but impossible to police in a fair, open, and transparent way.[29] Even if the Second Amendment did not exist, implementing the licensing system required by the convention would still be imprudent because it would worsen the problem of overcriminalization by extending federal criminal law to the recreational pursuits of millions of Americans.

Criminalizing Speech. Even more troubling, the convention criminalizes the “counseling” of any of the activities that it prohibits. In other words, the convention seeks to restrict the freedom of speech and requires signatories to afford each other “the widest measure of mutual legal assistance” in enforcing these restrictions. Under its provisions, it would be illegal for a citizen of a signatory foreign tyranny to say that his fellow victims should seek to arm themselves.

In the United States, such a restriction on speech is inherently undesirable and impossible under the First Amendment, and it would need to be the subject of a Senate reservation. The convention acknowledges this necessity by stating that the requirement to criminalize “counseling” is “[s]ubject to the respective constitutional principles and basic concepts of the legal systems” of the signatories.[30]

The Senate would need to enter two additional reservations: The U.S. will not provide any legal assistance to any investigation by signatories of supposed crimes based on the “counseling” of activities prohibited by the convention, and the U.S. will not extradite foreign nationals for exercising their free speech rights, even if other signatories regard their speech as an extraditable offense. However, such reservations, even if their validity were universally accepted, would not fully resolve the problem.

First, by ratifying the convention, the U.S. would be approving the creation of international legal instruments that restrict free speech. This is undesirable both on principle and because it would give dictatorial governments (for example, the Chávez regime in Venezuela) legal justification to curtail free speech on the grounds that they are only fulfilling their international obligations. Of course, dictators will curtail free speech in any case, but the U.S. should not give them legal sanction for their tyranny.

Both conservatives and liberals, including the Obama Administration, have opposed other international instruments, such as the U.N.’s effort through the Durban Review Conference to prevent the “defamation of religion,” that sought to curb free speech for the sake of other supposedly desirable ends.[31] The convention embodies a philosophy on free speech that has been widely rejected in the U.S. because of the correct perception that it is contrary to American freedoms and the American desire to see those liberties flourish abroad as well as at home.

Second, the convention’s subject raises particular concerns about its restrictions on speech. In a democracy, politics must proceed through the democratic process. Under a tyranny, the right of rebellion applies. The Founding Fathers appealed to this right when they broke away from Great Britain in 1776. By criminalizing the “counseling” of any of the measures that it defines as illegal, the convention strikes a blow against the efforts of citizens of foreign countries to resist tyrannical authoritarian and Marxist–Leninist leaders.

Under the convention, Patrick Henry’s famous “Give me liberty or give me death” oration in 1775—with its claim that “An appeal to arms and to the God of hosts is all that is left us!”—could be ruled illegal in a signatory that lacked protections akin to those of the First Amendment.[32] The existence of First Amendment protections in the United States is no reason for the U.S. to offer aid and comfort to regimes that would deny the freedom of speech in other countries.

Third, while the First Amendment protects the free speech rights of Americans and foreign nationals living in the United States, it would not protect exiles who speak in the U.S. and then travel to an OAS member state that is less vigilant in protecting free speech and less willing to reject extradition requests. The convention thus creates a chilling effect on free speech throughout the hemisphere, against which the First Amendment offers only partial and limited protection. Other OAS member states may have assented to this by signing and ratifying the convention, but the Senate should consider carefully before doing likewise.

Weakening First Amendment Protections. It is well-established legal doctrine in the United States that nothing, not even a signed and ratified treaty, can override the Constitution. Thus, the First Amendment would protect the right of Americans to counsel measures or actions that violate the convention.

However, Koh and other Administration figures have argued that when the First Amendment’s existence creates difficulties for foreign states, it is an example of (supposedly undesirable) American exceptionalism. In such cases, Koh has argued that the Supreme Court should reinterpret the First Amendment, and indeed the entire Constitution, in order to weaken it. According to Koh, judges should “construe the Constitution to invalidate domestic rules that now violate clearly established international norms.”[33]

The convention’s counseling provision fits Koh’s conditions exactly: It seeks to restrict speech inside signatories, including the United States, so that this speech does not disrupt the affairs of other states. This is embodied in a hemispheric convention that, in Koh’s view, is becoming a “clearly established international norm.” Koh has endorsed the convention enthusiastically as “the best model” to promote “the legal, political and social internalization of…[an] emerging international norm [against illicit arms transfers] into domestic legal systems.”[34]

Koh’s use of the term “norm” indicates that the convention is part of the broader agenda of legal transnationalism, which seeks to replace lawmaking through sovereign, democratic nation-states with norm-making by transnational nongovernmental organizations, bureaucrats, and lawyers.[35] Creating clashes between treaty obligations and the Constitution is part of the transnationalist strategy to erode constitutional freedoms that the transnationalists find objectionable. In the case of the convention, the existence of these clashes is ample reason to regard it with caution.

Questioning the Validity of Reservations. Koh has also questioned the legal validity of Senate reservations, which would be necessary to clarify that the Senate will not accept any restrictions on the First Amendment rights of Americans or foreign nationals in the U.S.[36] This is particularly troubling because Koh, as the State Department’s lawyer, is responsible for presenting testimony to the Senate as it considers reservations during the advice and consent process. There would be a serious conflict between Koh’s previously expressed views on reservations—coupled with his prior vigorous support for the convention— and the Senate’s duty to uphold freedom of speech as a constitutionally protected right and to scrutinize the convention with care.

Wide-Ranging Basis for Extradition. As part of the convention’s promotion of international cooperation, Article 17, “Mutual Legal Assistance,” requires signatories to “afford one another the widest measure of mutual legal assistance” in investigating the indictable offenses defined by the convention. These offenses are wide-ranging, including “participation in, association or conspiracy to commit, attempts to commit, and aiding, abetting, facilitating, and counseling the commission” of “the illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms, ammunition, explosives, and other related materials.” Article 19, “Extradition,” creates the legal basis for extradition based on any of these offenses between signatories.[37]

If the entire OAS membership were firmly democratic, this requirement would be less troubling, although aspects would still be unacceptable. Yet a number of anti-U.S. nations—Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela—are OAS members and signatories of the convention.[38] If the U.S. ratifies the convention, it will be required to afford legal assistance to the anti-American Venezuelan regime and to consider its extradition requests whenever the regime finds it convenient to claim that exiled opponents who have taken refuge in the U.S. have committed offenses—including those related to free speech— under the convention.

The U.S. would be within its rights to reject such extradition requests and would almost certainly do so. However, by doing so, the U.S. would open itself to charges that it is not living up to the convention’s requirements. Because the treaty contains obligations that the U.S. does not intend to fulfill, this problem is inescapable. The Senate should consider carefully before placing the U.S. in this invidious position.

Necessary Reservations

If the Senate considers the convention, it needs to enter a number of reservations to specific provisions in the convention to limit the risks to American freedoms and U.S. sovereignty.

Non-Self-Executing. It is unclear whether the convention is self-executing or will require legislation to enact its provisions. Koh argues that the “practice of prospectively declaring human rights treaties non-self-executing” is “unsound,” but the convention’s statement that signatories should “adopt the necessary measures” to bring it into effect strongly implies that it is not self-executing and that Congress would need to pass implementing legislation to give effect to the convention.[39]

However, the convention is not explicit on this point. In most cases, self-executing treaties are undesirable because they deprive Congress, and thus the American people, of the power to decide how to carry out their international obligations in a manner consonant with the Constitution.

If Koh’s doctrine prevailed in this case, it would have implications for both the First and Second Amendments: The convention’s counseling provision would immediately conflict with the First Amendment, while the authority the convention would grant to the ATF would allow it to issue the required regulations without approval from the U.S. House of Representatives. Such an action would almost certainly result in a court challenge.

The U.S. legal doctrine that the Constitution would prevail in any such challenge and the absence of any enforcement mechanism in the convention to implement its restrictions on free speech do not therefore make it acceptable to ratify the convention without reservations. Failure to enter reservations would give ground to the transnationalist strategy.

Therefore, if the Senate considers the convention, it should enter a reservation that clearly states that Koh’s doctrine does not apply, that the convention does not by itself create any cause of legal action against free speech or in any Second Amendment context, and that it requires passage of implementing legislation to enter into effect.

Precluding Creation of Privately Enforceable Rights. The convention does not expressly exclude the right of individuals and private entities to sue to enforce the convention or to assert rights under it. It might therefore be held to create both a large class of potential litigants—any opponent of gun ownership—and an opening for lawsuits that would seek to use the convention to enforce the most stringent interpretation of its terms, which would raise both First and Second Amendment issues.

A divided Supreme Court found in Medellin v. Texas that “treaties do not create privately enforceable rights in the absence of express language to the contrary,” and the convention contains no such express language.[40] Nonetheless, if it considers the convention, the Senate should act consistently with the well-established principles reaffirmed in Medellin by entering an explicit reservation to the effect that the convention creates no privately enforceable rights.

A Summary of First Amendment Concerns. At a minimum, the Senate will have to enter five reservations to the convention on grounds partly or wholly related to the First Amendment. More broadly, the convention’s limits on free speech are obnoxious domestically and undesirable internationally because of the aid and comfort they would give to tyrannies, regardless of any reservations applied by the Senate. Because the U.S. cannot fulfill the convention’s terms in their entirety, ratifying it would immediately place the U.S. in the position of having to defend its declared noncompliance with freely accepted obligations—a situation that is never desirable.

Finally, the Administration’s leading authority on international law has explicitly identified the convention as a mechanism to achieve his goal of reinterpreting the Constitution. The convention is therefore incompatible with the First Amendment and is part of a campaign to limit First Amendment rights of Americans and foreign nationals in the United States. On these grounds alone, the convention poses a grave prudential risk.

Illegitimate Restraints on U.S. Sovereignty. The convention poses a further challenge to American sovereignty. In essence, a treaty is an agreement between sovereign states. To enter into a treaty is to agree to a contract. The terms of the contract restrain the exercise of American sovereignty in exchange for restraint by the other signatories. Because treaties must be negotiated, signed, and ratified by the U.S. government, they are entirely compatible with American self-government. Indeed, they are an expression of it because the treaty restraints are reciprocal, freely chosen, and democratically accepted.

In the United States, a properly signed and ratified treaty, accompanied by its implementing legislation, becomes part of U.S. law. This is why it is important for the U.S. to enter only into treaties that it intends to uphold conscientiously.

Problems arise when other signatories do not keep their side of the contract. In theory, this entitles the U.S. to renounce the treaty, but in practice, the U.S. rarely does so. This is particularly true of multilateral treaties, such as the convention, where the default of one or even many of the signatories is not held to release the U.S. from its obligations. The result is that the U.S.’s sovereignty continues to be constrained, but this constraint is not reciprocated. Such one-sided constraints are illegitimate.

The convention will likely produce such illegitimate constraints. In ratifying it, the U.S. would essentially be relying on Chávez’s Venezuela and Evo Morales’s Bolivia, among others, to keep their word. Advocates of the convention ignore the implausibility of relying on these regimes because they value the policies the convention embodies.[41] That is a misuse of the treaty-making process, which exists to negotiate agreements that effectively bind all signatories, not just the United States.

Supporters of the convention therefore argue that the U.S. should ratify it because the “United States’ absence as a treaty participant has undermined the success of CIFTA and given a pass to those who willfully chose to ignore it.”[42] This is a fallacious vision of international law and politics because it implies that other states are failing to live up to the responsibilities that they have freely accepted by signing the convention simply because the U.S. has exercised a similar freedom by not ratifying. If the convention lacks credibility, this is a problem with the convention itself and the states that have signed it. America’s leadership role does not obligate it to ratify treaties simply because other countries have done so and are disappointed with the results.

A Non-Binding Treaty Body. Finally, the convention creates a Consultative Committee of member states. The committee’s decisions would be recommendations, not requirements, and as long as the committee restricts itself strictly to this role of issuing entirely non-binding recommendations, it poses no direct threat to American sovereignty. Article 20, “Establishment and Functions of the Consultative Committee,” calls on the committee to supply “technical assistance” to “relevant international organizations,” a requirement that is reiterated in Article 15, “Exchange of Experience and Training,” and Article 16, “Technical Assistance.”[43]

However, this is a backdoor through which the committee’s members and members of other international organizations could pressure the U.S. into practical compliance with the U.N.’s proposed Arms Trade Treaty, which seeks to establish “common international standards for the import, export, and transfer of conventional arms.”[44] The U.S. would not be obligated to comply with the committee’s requests, but failure to do so would again put the U.S. in the position of not fulfilling its freely accepted international obligations. The Senate would need to enter a reservation stating that the U.S. would supply information and assistance on a purely voluntary, case-by-case basis.

Questionable Relevance in the Western Hemisphere

Those seeking ratification of the convention must also ask whether it will truly address the security challenges that the U.S. and other states face in the Western Hemisphere. The primary reason that the Obama Administration has revived the treaty at this point is that the Administration views it as a deliverable that would send a political and diplomatic signal to Mexico and other OAS members that the U.S. is serious about supporting Mexico’s authorities in addressing the ongoing challenge to law and order in Mexico.

President Clinton and President Ernesto Zedillo of Mexico first negotiated the convention in 1997, using it as a signaling device during a previous episode of heightened concern over drug-related violence in Mexico. As President Clinton proudly asserted in his remarks, the convention was “conclude[d]…in record time,” taking only seven months from a public agreement to negotiate in May 1997 to signing in November of that year.[45]

An arms control agreement of such scope and complexity would normally take years to negotiate. The rapidity with which it was concluded raises doubts about the care with which it was negotiated and the extent to which it was ever intended as a serious diplomatic response to illegal arms trafficking.

Lack of Statistical Support. The convention promises to serve as a legal mechanism for stemming the flow of firearms into Mexico, where weapons legally purchased in the U.S. but illegally exported to Mexico help to fuel drug violence. Supporters argue that 87 percent of the guns seized in Mexico from drug cartels originate in the U.S.[46] However, this figure is not supported by the data from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) that they cite.

Jess T. Ford, Director of International Affairs and Trade at the GAO, testified before the House Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere on June 19, 2009, that it “is impossible to know how many firearms are illegally trafficked into Mexico in a given year.”[47] It is therefore impossible to know what proportion of firearms is illegally trafficked into Mexico from the U.S. in a given year. Of the weapons that have been seized in Mexico and given to the ATF for tracing from 2004 through 2008, the GAO reports that approximately 87 percent originated in the U.S. However, this number says nothing about the percentage of guns seized in Mexico that originated in the U.S., because the ATF did not trace the majority of guns seized in Mexico.

The figure shows only that over the past five years, Mexican authorities have been 87 percent accurate in their preliminary assessment that a seized weapon originated in the U.S. and should be traced through the U.S.’s eTrace system. It says nothing about the percentage of guns in Mexico that originated in the U.S. because, as Ford stated, no one knows how many guns enter Mexico illegally, much less how many are acquired or manufactured illegally inside Mexico. Mexican officials have occasionally refused ATF requests to trace the guns found in huge arms caches or used in the murders of police officers.[48] It is reasonable to infer that these requests were refused because ATF tracing might have uncovered arms smuggling operations that corrupt Mexican government officials wished to protect.

Figures like “87 percent” sound impressive, but actual numbers are more illustrative. According to the GAO, the number of guns seized in Mexico that have been traced back to the U.S. has ranged from 5,260 in 2005 to 1,950 in 2006 to 3,060 in 2007 to 6,700 in 2008.[49] Information on the total number of guns seized in Mexico annually is much less precise, but a recent study reported in mid-2009 that 55,000 guns have been seized “since 2006.”[50] This implies that only about 12,000 of the seized guns (the total for 2006, 2007, and 2008 plus an unknown number for part of 2009) were ultimately traced back to the U.S.

In other words, no more than 25 percent of the seizures were traced back to the U.S. Thus, according to the data cited by some of the convention’s strongest supporters, it is misleading to argue that “the most significant source of illegal firearms in Mexico is guns purchased in the United States and then smuggled into Mexico.”[51]

Mexico’s problems are fundamentally homegrown, but this implies that U.S. ratification of the convention, especially as it is intended as a signal, will not substantively improve the situation on the ground in Mexico. More broadly, it points out that, while U.S. ratification may demonstrate U.S. commitment to the convention, it does nothing to guarantee that other member states, which often have weak enforcement regimes and different political agendas, will vigorously enforce its requirements. For example, Venezuela is acquiring its own manufacturing plant for AK-47s.[52] It is unlikely to abide by the convention’s provisions.

A Poor Track Record. The convention’s record in enforcement and utility should also be considered. When current Colombian President Alvaro Uribe took office at the height of the conflict in 2002, a range of armed non-state actors, notably narco-terrorists belonging to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and paramilitaries of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), were maintaining field armies of more than 50,000 heavily armed combatants. Yet the OAS failed to take a single action to sanction or punish those who provide arms to these illicit organizations. Arms shipments continue today, with weapons arriving from military stocks throughout the Americas.[53] The OAS does not even consider the FARC to be a terrorist organization.

Venezuela’s response to the Colombian military’s capture of sophisticated, Swedish-made AT-4 anti-tank weapons from the FARC illustrates the increasing lack of cooperation. Both Colombia and Venezuela have ratified the convention. Yet when Colombian officials sought an explanation through diplomatic channels as to how the weapons reached the FARC, Venezuela and Hugo Chávez responded with silence, denial, outrage, and finally an explanation that the FARC had stolen the weapons years earlier from a Venezuelan arsenal.[54] Venezuela made no commitment to Colombia or the OAS to cooperate in an investigation or fact-finding process. In an increasingly polarized hemispheric environment, noncooperation on critical matters relating to the illicit sale and transfer of small arms and light weapons remains distressingly the norm.

Superior Alternatives to the Convention

If it declines to ratify the convention, the U.S. has alternative and more effective ways of combating arms trafficking in the Western Hemisphere and around the world. In fact, the U.S. already operates a wide range of bilateral programs that confront the problems that the convention supposedly seeks to address, ranging from assistance with stockpile destruction to advice on the creation of effective export controls to training of foreign law enforcement officers.[55]

By contrast, the convention is an unenforceable, one-size-fits-all model that applies to the entire hemisphere, even though its supporters primarily justify it in reference to U.S.–Mexican relations. The goal of ending the illegal transfer of arms across the U.S.–Mexico border implies tight border controls in all areas, but no border can stop arms while allowing any meaningful level of illegal immigration. Supporters of the convention should therefore prioritize border control.

Yet Mexican officials have been credibly charged with turning a blind eye to and even encouraging illegal entry into the United States, while the Obama Administration’s immigration policy places amnesty for illegal immigrants on the same priority level as enforcing the existing laws.[56] This is an incoherent stance that again raises the suspicion that the convention is intended at best as a signal to Mexico, not as a substantive treaty.

Questionable Relevance to U.S. Border Enforcement. There is a final country in the Western Hemisphere where the convention will be of questionable relevance: the United States. The central purpose of the convention is to control the cross-border sale and transfer of arms. The regulations on domestic manufacturing and assembly are purportedly necessary only to achieve this aim. However, the U.S. already requires a license for the import or export of arms.

Enforcement is what matters, not how many treaties are signed. A basic failing of the transnationalist vision is the belief that drafting a treaty is the same as actually solving a problem. Supporters of national sovereignty, on the other hand, are reluctant to ratify the wide-ranging convention precisely because they take enforcement seriously. Instead, they prefer to emphasize the effective enforcement of existing law that controls arms imports and exports.

Better Alternatives. The convention, like other inter-American agreements on challenges such as drug trafficking and corruption, will fall well short of its intended mark of robust, effective, multilateral cooperation, even assuming that such multilateral cooperation were necessary to address bilateral issues on the U.S.–Mexican border. The current environment for the convention is particularly poor because the growing schism within the OAS between the U.S. and its friends and the Hugo Chávez and Raul Castro–oriented Left have reduced levels of hemispheric cooperation and the OAS’s desire to speak out assertively in favor of democracy and human rights.[57]

The alternative is to rely on bilateral cooperation between the U.S. and other states in the Western Hemisphere that are genuinely interested in reducing arms trafficking and improving the security of government armories. Such cooperation is fully in the U.S. interest. Because it is voluntary and therefore includes only willing partners who are serious about improving their governance, it offers greater prospects of success than are offered by the convention. It also poses no threat to U.S. sovereignty or constitutional freedoms.

What the U.S. Should Do

Having been signed and ratified by most OAS members, the convention will not be redrafted. A crucial Administration appointee has expressed doubt about the validity of Senatorial reservations, and five reservations would be needed to protect U.S. liberties under the First Amendment alone. The convention’s expansive definition of “manufacture or assembly” and its treatment of security measures, record keeping, and information exchange raise even more serious concerns related to the Second Amendment and the growing problem of overcriminalization that the Senate would need to address with substantial reservations asserting that U.S. federal law remains in effect and unaltered.

The Senate should recognize that U.S. ratification will necessitate entering multiple reservations. The Senate would need to enter one or more reservations against 12 of the 29 articles in the convention: Article 1, “Definitions”; Article 4, “Legislative Measures”; Article 7 “Confiscation or Forfeiture”; Article 8, “Security Measures”; Article 9, “Export, Import, and Transit Licenses or Authorizations”; Article 12 “Confidentiality”; Article 13, “Exchange of Information”; Article 15, “Exchange of Experience and Training”; Article 16, “Technical Assistance”; Article 17, “Mutual Legal Assistance”; Article 19, “Extradition”; and Article 20, “Establishment and Functions of the Consultative Committee.” The Senate would also need to enter reservations against the Preamble and the OAS’s Model Legislation.

The Senate should recognize that these reservations are wide-ranging and incompatible with the convention’s purpose. While the use of reservations in the advice and consent process is legal and correct, as acknowledged in Article 24, “Reservations,” it is also commonly accepted as a principle of diplomacy that reservations cannot have the effect of substantially voiding central elements of a treaty. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties[58] expresses this obligation to refrain from reservations that are “incompatible with the object and purpose of the treaty.”[59] The convention contains a similar clause in Article 24.[60] Because the reservations the U.S. would need to enter would touch directly on both the offenses the convention seeks to define and the cooperation it seeks to promote, they could rightly be held to be incompatible with its object. Thus, the U.S. can neither properly ratify the convention with such reservations nor safely ratify it without these reservations.

The Senate should not enter into unenforceable treaties, especially those that pose risks to U.S. rights. The convention creates serious legal obligations that are neither symbolic nor minor nor technical. International agreements such as the convention should never be used as symbolic gestures, as the current Administration is seeking to do. Treaties are too important to be misused in this way. This is especially true in arms control, and the convention is ultimately an arms control treaty. It is a serious error to treat arms control with the same disregard for enforcement that is commonly displayed by human rights treaties.

This failure of human rights treaties to address enforcement seriously is wrong, but in arms control treaties, it is both wrong and dangerous because an ineffective treaty shields the activities of wrongdoers and hence becomes a security threat in itself.[61] Like the U.N.’s Arms Trade Treaty, for which CIFTA is an inspiration, the convention will give dictatorial states such as Venezuela the legal cover to subvert their democratic neighbors. In addition, the convention would pose a significant prudential risk to rights in the United States, including those guaranteed by the First and Second Amendments.

The Senate should recognize that the convention is destructive of U.S. sovereignty. The convention’s faults are serious. However, the argument that the U.S. should ratify the convention simply to fall in line with the rest of the OAS is even more fundamentally objectionable. It implies that the U.S. should act on matters within its national competence not because it has decided to do so, but because other states have already acted. It therefore advances the idea that self-government in the U.S. should proceed under the guidance and suggestion of other states and, ultimately, of the “international community.” This idea is destructive of national sovereignty, which is inextricably linked to the inherent right of self-government.

The Right Course of Action

The U.S. has negotiated an onerous convention that will be broadly damaging if ratified. The convention’s obligations should not be dismissed as too minor to matter. They are, in fact, major. In any event, ratification would start the U.S. down a path toward accepting even more onerous obligations when the convention fails to achieve its aims.

Even the convention’s requirements as they exist today would necessitate a substantial expansion of federal authority into realms that are unrelated to the convention’s purported aims, an expansion that would be administratively complex and that would discredit the convention and treaty-making process more broadly. For those who genuinely believe in the value of the treaty-making process, this is undesirable. Few developments could damage the institutions of diplomacy more than the kind of overreach demonstrated by this convention.

As President Clinton acknowledged, the convention was drafted rapidly. This may account for both its puzzling lack of clarity and the inclusion of many requirements that the Senate, regardless of political complexion, would never eagerly accept.

For those who are seriously interested in the convention’s object and in effective diplomacy more broadly, this convention clearly demonstrates that the U.S. needs to negotiate better treaties. The U.S.’s failure to do so on this occasion has put the convention’s supporters in the contradictory but revealing position of arguing that “U.S. ratification [of the Convention] would require no new laws…[and] only minor changes” in regulation, but that the convention would nonetheless “provide another tool that establishes practical steps to deal with the flow of weapons between the United States and Mexico.”[62]

The right course of action, therefore, is for the U.S. to continue, as it currently does, to make and enforce its own laws on matters relevant to the convention, to operate its existing programs that seek to combat the illicit traffic in arms, and to cooperate on a bilateral basis. The U.S. and other nations with similar aims have employed this approach with great success in the Proliferation Security Initiative.

Ted R. Bromund, Ph.D., is Senior Research Fellow in the Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom, a division of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for International Studies, at The Heritage Foundation. Ray Walser, Ph.D., is Senior Policy Analyst for Latin America in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign Policy Studies, a division of the Davis Institute, at The Heritage Foundation. David B. Kopel is Director of Research at the Independence Institute in Colorado.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

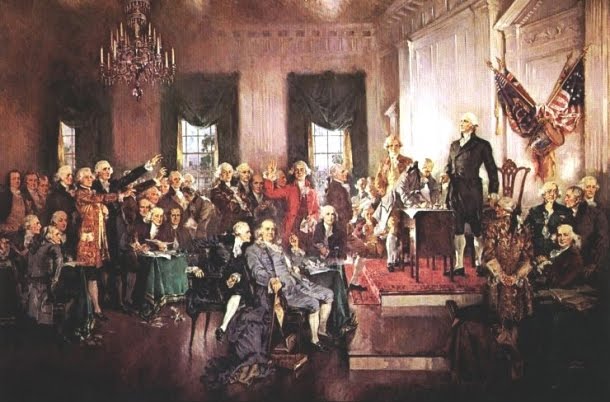

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment