From The American Thinker:

November 20, 2010

George W. Bush: His Own Man

By Matthew May

George W. Bush is no Ulysses S. Grant.

In introducing his new memoir Decision Points, President Bush reveals his reliance upon the example of one of his predecessors' literary approach. Utilizing George W. Bush's presidential identification process, "18" set the standard for the presidential memoir and all autobiography. Grant's work was impressive on its own, but the fact that he wrote it in a literal race against death and destitution makes it an astonishing achievement. Grant finished the final chapter days before he died. Mark Twain delivered the verdict:

The fact remains and cannot be dislodged that General Grant's book is a great, unique, and unapproachable literary masterpiece. There is no higher literature than these modest, simple Memoirs. Their style is at least flawless, and no man can improve upon it.

No man has, including "43." But he makes no such claim of intent. President Bush simply writes that like Grant, he wishes his memoir to serve as a resource for future generations studying this significant era in American history. This approach, a resource explaining and elaborating upon assembling personnel and the momentous decisions unlike most any other president's, makes the book invaluable. Like his approach to governance, the author lays out his objective and follows through without straying as best he can.

President Bush turns the neat trick of presenting the self-portrait of a steadfast, humble, Christian man comfortable in his own skin and cognizant of the weight and import of his decisions without braggadocio or bombast, but with blunt clarity. He tells stories of himself in his endearing self-deprecating manner, especially how his reliance on alcohol made him clownishly immature and how he vanquished it with faith and resolution, as well as amazing strength provided by a remarkable family. Perhaps this is a deficiency emblematic of our self-confessional culture. But it gives fascinating insight into the background and foundation of only the second and perhaps unlikeliest person to attain the presidency after his father held the office (the first would be "6").

What historian James McPherson wrote of Grant's Memoirs can also be said of Decision Points:

Although he kept himself at the center of the story, the memoirs exhibit less egotism than is typical of the genre. Grant is generous with praise of other officers and sparing with criticism, carping, and backbiting. He is also willing to admit mistakes[.]

This willingness to revisit decisions and admit error is especially evident in the passages chronicling the aftermath of the capture of Saddam Hussein in December 2003. Rather than bask in deserved light for ridding the world of one of the most brutal tyrants it has ever seen, the president outlines "what went wrong in Iraq and why" by documenting the two key errors he and his administration made that slowed the progress.

Lesser men would have dealt much more harshly with people like Harry Reid or Pete Stark, who on the House floor accused George Bush and his warmongering cronies of laughing over the corpses of dead American servicemen. He could have written about how offensive his successor's lecturing about "putting away childish things" on Inauguration Day 2009 was then and how it was but a glimpse of things to come.

George W. Bush's refusal to do so is a mark of the Christian ethic by which he lives. It is the particular grace of this man, unwilling to engage in fruitless counterargument against fools. Instead, he presents the evidence matter-of-factly for the future to decide, such as Gerhard Schroeder's betrayal in 2002 over the use of force in Iraq and the roster of Democrats such as Kerry, Biden, Daschle, and Reid who passed the resolution to authorize war against Saddam Hussein amid the slowest "rush to war" in history. Almost certainly, George W. Bush has the human impulse to strike back. But those thoughts are left unsaid and unwritten.

The book could have done without some cringe-making construction peppered throughout such as "The seeds of that decision, like many others in my life, were planted in the dusty ground beneath the boundless sky of Midland, Texas." One wonders if there was an effort to set a world record for most uses of the word "roustabout" in the early going. Some of the passages seem rushed, and the president admits that the book is by no means exhaustive. The chapter on the president's decisions relating to the financial crisis of 2008 is unconvincing.

But most of the book is an interesting and sometimes thrilling look inside the presidency during a time of peril, strife, and controversy. The passages from September 11, 2001 and its aftermath are particularly moving, bringing to mind the anguish, rage, and fear that the president shared in unison with America. Rereading passages from his addresses at the time is to recall how eloquently and movingly George W. Bush spoke for the country. The book is the personal story of a man who found redemption in faith, unashamedly practices that faith on a daily basis, and retains a humility quite remarkable for any leader. If nothing else, the book is a primer for future presidents on how to function amid chaos, how to face a "day of fire," and how to revere the office and the protectors of our country.

Nobody will or should ever say that Decision Points is an unapproachable literary masterpiece. But the book is deserving of the success it is meeting and will be regarded among the best of the genre because it presents the man as he is: at peace with himself and his decisions and unwilling to let any man be the final judge of his life on earth.

Matthew May is the primary author of the forthcoming book Restoration: The God and Country Education Project. He welcomes comments at matthewtmay@yahoo.com.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

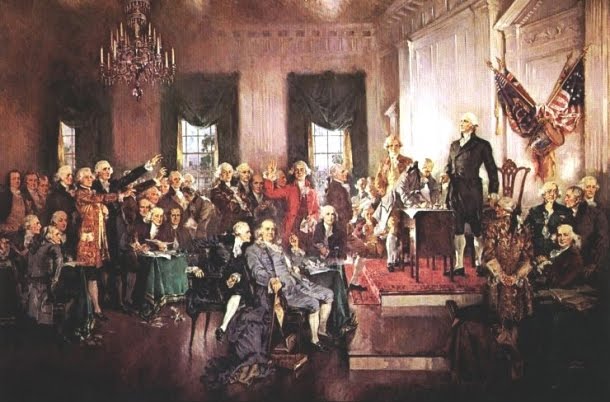

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

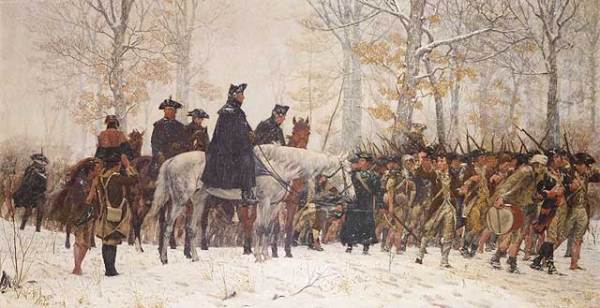

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment