From US News and World Report and Lou Dobbs:

Mort Zuckerman: America's Love Affair With Obama Is Over

The administration is running out of time to lower unemployment and fix the economy

By Mortimer B. Zuckerman

Posted: November 5, 2010

Print Share This

It was the worst of times for the Democrats and the best of times for the Republicans—almost. The GOP did not succeed in capturing the Senate, or dethroning the Democratic leader, but with an energy boost from the Tea Party movement it certainly reflected the anger and dismay of voters who see their country foundering at home and abroad.

The results represent a sharp rebuke to President Obama, who interpreted his 2008 "vote for change" as a mandate for changing everything and all at once. Right from the start, he got his priorities badly wrong, sacrificing the need to help create jobs in favor of his determination to pass Obamacare. It was the state of the economy that demanded genius and concentration, and it just did not get it. The president will now have to respond to public anger, not with anger management and, not, please God, with still more rhetoric. The unusually revealing exit polls spell it all out—how he re-energized the Republican Party, lost the independent center, and failed to overcome the widespread sense that the country is heading in the wrong direction.

The exit polls conducted by Edison Research for the National Election Pool show that the economy was the dominant issue, rated at 62 percent, while healthcare was only at 18 percent. Minority voters remained loyal (9 in 10 blacks and 2 in 3 among Hispanics), but everywhere else Obama was deserted. Independents and women fled the Democrats; among white women, no less than 57 percent chose the GOP. There are some surprises for the conventional wisdom. The case for creating more jobs by government spending was rated within a hair's breadth of reducing the deficit (37 percent to 39 percent) and opinion was evenly divided (33 to 33) on whether the stimulus had hurt or helped the economy. Voters registered their disapproval of Democratic control of Congress and of what the White House promised but failed to deliver. It is apparent that Obama didn't seem to have understood the problems of the average American.

[See a roundup of editorial cartoons about the 2010 campaigns.]

He came across as a young man in a grown-up's game—impressive but not presidential. A politician but not a leader, managing American policy at home and American power abroad with disturbing amateurishness. Indeed, there was a growing perception of the inability to run the machinery of government and to find the right people to manage it. A man who was once seen as a talented and even charismatic rhetorician is now seen as lacking real experience or even the ability to stop America's decline. "Yes we can," he once said, but now America asks, "Can he?"

The last two years have exposed to the public the risk that came with voting an inexperienced politician into office at a time when there was a crisis in America's economy, as the nation contended with a financial freeze, a painful recession, and two wars. The Democrats were simply not aggressive enough or focused enough in confronting the profound economic crisis represented by millions of ordinary Americans whose main concern was the lack of jobs.

Jobs have long represented the stairway to upward mobility in America, and the anxiety over joblessness became the dominant concern at a time when financial security based on home equity and pensions was dramatically eroding. No great speech is going to change the fundamental fact that millions of people are either jobless or underemployed at a time when only a quarter of the American population describes the job market as good.

Why did Obama put his health plan so far ahead of the economy? To do what the Clintons couldn't? His rush to do it sparked a broad resistance that has only spread since the bill was passed. The public sensed that healthcare was a victory for Obama, and maybe for the Democrats, but not for the country—and contrary to Democratic hopes, public support for the measure has continued to drop to as low as 34 percent in some polls. A significant majority, some 58 percent, now wish to repeal the entire bill, according to likely voters questioned in a late October poll by Rasmussen.

As political analyst Charlie Cook put it: "Every month, every week, every day that Washington seemed focused on healthcare instead of the economy frightened people. It seemed out of touch." It also seemed tone-deaf to the public's concern with unemployment, the cost of government, and the sense that America was declining in its ability to compete in the world. It made Obama's behavior seem as if he headed the most liberal wing of the Democratic Party in Congress, particularly when he allowed the major policies of his presidency to be written not by his cabinet or the White House staff but by the congressional leadership of Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid. Then he accepted the lopsided bills that emerged and the political corruption that accompanied them—the very processes he condemned during his campaign and that are so much distrusted by a broad section of the American public. Eighty-five percent of Americans were concerned about the cost of healthcare, but the administration focused on extending coverage.

The open purchasing of votes through the provision of special exemptions for five states and for unions, and concessions to many of the special interests in the Democratic Party, especially trial lawyers, symbolized the corruption of our politics. The 2009 omnibus spending bill alone contained 8,570 special earmarks like those that had so enraged the American public in the past. When lawmakers had no time to even read the bills, it gave the impression that what was important was passing anything, no matter how ineffectual. Obama had promised he would change "politics as usual." He changed it all right, but for the worse. The list of his additional programs only provoked the public's distaste for big government, big spending, and big deficits.

[See photos of the Obamas behind the scenes.]

Today the polls indicate that the president has reached a point where a majority of Americans have no confidence, or just some, that he will make the right decisions for the country. There isn't a single critical problem on which the president has a positive rating. It didn't help when he kept on and on asserting that he had inherited a terrible situation from the Bush administration. Yes, enough, and sir, the country elected you to solve problems, not to complain about them.

It did not help that the administration had completely lost the support of the business community, where virtually no one has a good word to say about the administration and where there is no go-to, high-level businessman in Obama's inner circle. The result was to make corporate America lose even more confidence in making investment decisions.

[See editorial cartoons about the economy.]

Obama's job approval rating has fallen well below 50 percent overall, but the numbers are lower among whites and even lower among working-class whites, whose revolt may be the defining characteristic of 2010 (counting even more than the rise of the mostly white and affluent Tea Party movement). These were the famous "Reagan Democrats." They felt that the economy was collapsing around them and that their president was out of touch. In addition, as those exit polls confirm, Democrats have for some time been losing vast pieces of their core constituencies among women, independents, college graduates, and the elderly.

As for the public's hope for bipartisanship, Obama's partisan approach was underlined by putting forth one of the most liberal budget programs in decades. This failure was captured most recently in a New York Times front-page story that reported that for the first 18 months of his presidency, Obama would not meet one-on-one with the Republican leader in the Senate, Mitch McConnell. This is not bipartisanship, and inviting a few Republican congressmen to the White House for the Super Bowl is no answer.

The public disillusionment has now hardened. In a Quinnipiac poll this summer, only 28 percent of white voters said they would back Obama for a second term if the election were held then. Still, those results do not mean the public will go Republican next time. It depends on the candidate and the party. A centrist Democrat could win again—someone like retiring Sen. Evan Bayh, who sets a better course for the party in a New York Times op-ed. "A good place to start would be tax reform. Get rates down to make American businesses globally competitive," he writes. "Simplify the code to reduce compliance costs and broaden the base. . . . Ban earmarks until the budget is balanced [and] support a freeze on federal hiring and pay increases."

The love affair with Obama is over. The jobless will be the new swing voters. Unemployment, underemployment, and collapsing home equity will be the leading factors in 2012. The administration hopes the economy will have improved significantly by then, but it is running out of time and out of the confidence of the American public.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

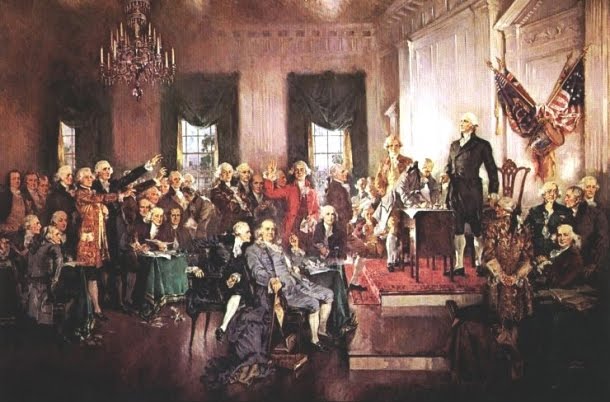

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment