From Campaign For Liberty:

Public Works and Pyramids

By William Anderson

View all 51 articles by William Anderson

Published 10/15/10

Printer-friendly version

When New Jersey Governor Chris Christie recently pulled out of the proposed Hudson River rail tunnel, angst gripped the editorial pages of the New York Times and elsewhere. Columnists and some economists declared in effect: We need the tunnel! It will provide jobs! We have too much congestion! This decision is shortsighted!

For example, Bob Herbert bewails that the government can do all sorts of very costly things, but "can't seem to build a railroad tunnel to carry commuters between New Jersey and New York." He continues:

The United States is not just losing its capacity to do great things. It's losing its soul. It's speeding down an increasingly rubble-strewn path to a region where being second rate is good enough. [Emphasis added.]

The railroad tunnel was the kind of infrastructure project that used to get done in the United States almost as a matter of routine. It was a big and expensive project, but the payoff would have been huge. It would have reduced congestion and pollution in the New York-New Jersey corridor. It would have generated economic activity and put thousands of people to work. It would have enabled twice as many passengers to ride the trains on that heavily traveled route between the two states.

Herbert fails to mention that Christie vetoed the project because huge cost overruns would have imposed a crushing burden on New Jersey taxpayers. Paul Krugman (not surprisingly) counters that getting rid of what economists call "externalities" (such as traffic congestion) would magically transform the multibillion-dollar expenditures from red to black ink. Therefore, a costly boondoggle always can be justified as a net plus for taxpayers. Krugman writes:

It was a destructive and incredibly foolish decision on multiple levels. But it shouldn't have been all that surprising. We are no longer the nation that used to amaze the world with its visionary projects. We have become, instead, a nation whose politicians seem to compete over who can show the least vision, the least concern about the future and the greatest willingness to pander to short-term, narrow-minded selfishness.

I hate to interrupt this self-righteous pity party, but if there ever were a "Not So Fast" moment, this is it. A public-works project such as the proposed tunnel makes sense if over time the marginal benefits outweigh the marginal costs. If they do not, then it provides a benefit to some at the expense of others, something the ancients might have called "unjust." Since the output of public works is not priced in the market, how would we know if costs exceed benefits?

In contrast, the existing rail tunnel under the Hudson was built by the Pennsylvania Railroad a century ago, and despite the modern declarations that government must provide such things, the company did it because it was good business. There was none of the convoluted "this lowers externalities" arguments we hear from people like Krugman as justification for the rail tunnel. The old tunnel was governed in large part by market prices so there was a market-driven return on investment.

Today, we see economic analysis turned on its head. Projected cost overruns suddenly are justified because "they provide jobs," as though higher costs mean more wealth created. Writes Herbert:

The railroad tunnel project, all set and ready to go, would have provided jobs for 6,000 construction workers, not to mention all the residual employment that accompanies such projects. What we'll get instead, if it is not built, is the increased pollution and worsening traffic jams that result when tens of thousands of commuters who would have preferred to take the train are redirected to their automobiles.

Don't forget, this was a multibillion-dollar project to aid a subsidized industry, which means that in the end, it would have enabled the consumption of more wealth than it allegedly would create. Furthermore, the history of such projects in New York is that they become financial black holes, and this likely would have been one.

Egypt's pyramids, while today drawing tourists and archeologists, were in their day just another giant public-works project that ultimately lowered the standard of living for ordinary Egyptians. High-cost projects can be impressive and even have a wonder all their own, like Hoover Dam. However, if they use more wealth than they create, they are a burden, period.

Copyright © 2010 Foundation for Economic Education

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

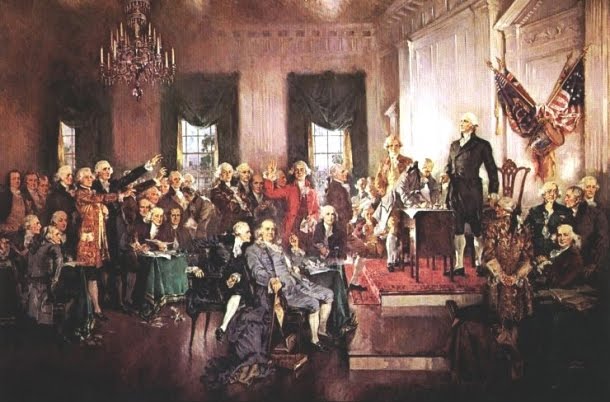

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment