From The New Ledger:

Allowing a Challenge to Obamacare to Go Forwardby Pejman Yousefzadeh

It is most gratifying to see this decision by Judge Roger Vinson of the Northern District of Florida, allowing a challenge to health care “reform” to go forward on Constitutional grounds. Tim Sandefur quotes a significant passage from Judge Vinson’s opinion:

ADVERTISEMENT

The individual mandate applies across the board. People have no choice and there is no way to avoid it. Those who fall under the individual mandate either comply with it, or they are penalized. It is not based on an activity that they make the choice to undertake. Rather, it is based solely on citizenship and on being alive. As the nonpartisan CBO concluded sixteen years ago (when the individual mandate was considered, but not pursued during the 1994 national healthcare reform efforts): “A mandate requiring all individuals to purchase health insurance would be an unprecedented form of federal action. The government has never required people to buy any good or service as a condition of lawful residence in the United States.” Of course, to say that something is “novel” and “unprecedented” does not necessarily mean that it is “unconstitutional” and “improper.” There may be a first time for anything. But, at this stage of the case, the plaintiffs have most definitely stated a plausible claim with respect to this cause of action.

Ilya Somin has some more good quotes–including the following one on the issue of whether the individual mandate may be imposed because it is a tax (recall that the Obama Administration denied that the individual mandate was a tax when they were working to pass health care reform, but then decided to call it just that when seeking to justify it on Constitutional grounds in the courts):

Because it is called a penalty on its face (and because Congress knew how to say “tax” when it intended to….), it would be improper to inquire as to whether Congress really meant to impose a tax. I will not assume that Congress had an unstated design to act pursuant to its taxing authority, nor will I impute a revenue-generating purpose to the penalty when Congress specifically chose not to provide one. It is “beyond the competency” of this court to question and ascertain whether Congress really meant to do and say something other than what it did.

As the Supreme Court held by necessary implication, this court cannot “undertake, by collateral inquiry as to the measure of the [revenue-raising] effect of a [penalty], to ascribe to Congress an attempt, under the guise of [the Commerce Clause], to exercise another power.” See Sonzinsky, supra, 300 U.S. at 514. This conclusion is further justified in this case since President Obama, who signed the bill into law, has “absolutely” rejected the argument that the penalty is a tax…. To conclude, as I do, that Congress imposed a penalty and not a tax is not merely formalistic hair-splitting. There are clear, important, and well-established differences between the two. See Dep’t of Revenue of Montana v. Kurth Ranch, 511 U.S. 767, 779–80, 114 S. Ct. 1937, 128 L. Ed. 2d 767 (1994) (“Whereas [penalties] are readily characterized as sanctions, taxes are typically different because they are usually motivated by revenue-raising, rather than punitive, purposes.”); Reorganized CF&I Fabricators of Utah, Inc., supra, 518 U.S. at 224 (“‘a tax is a pecuniary burden laid upon individuals or property for the purpose of supporting the Government,’” whereas, “if the concept of penalty means anything, it means punishment for an unlawful act or omission”).

Equally notable is Judge Vinson’s observation that invocations of the Commerce Clause and the Necessary and Proper Clause notwithstanding, they have never been used to justify the kind of sweeping legislation presented to the country in the form of health care reform:

I have read and am familiar with all the pertinent Commerce Clause cases, from Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1, 6 L. Ed. 23 (1824), to Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1, 125 S. Ct. 2195, 162 L. Ed. 2d 1 (2005). I am also familiar with the relevant Necessary and Proper Clause cases, from M’Culloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316, 4 L. Ed. 579 (1819), to United States v. Comstock, — U.S. —, 130 S. Ct. 1949, 176 L. Ed. 2d 878 (2010). This case law is instructive, but ultimately inconclusive because the Commerce Clause and Necessary and Proper Clause have never been applied in such a manner before. The power that the individual mandate seeks to harness is simply without prior precedent.

To be sure, no one ought to get too excited over this ruling; all that it means is that the suits against the enactment of health care reform can go forward, not that they have been found Constitutional. But the fact that the suits were not dismissed by Judge Vinson says something significant about them. With Judge Vinson’s opinion, the argument that health care reform will be found unconstitutional has gone from being laughable to suddenly being taken seriously.

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

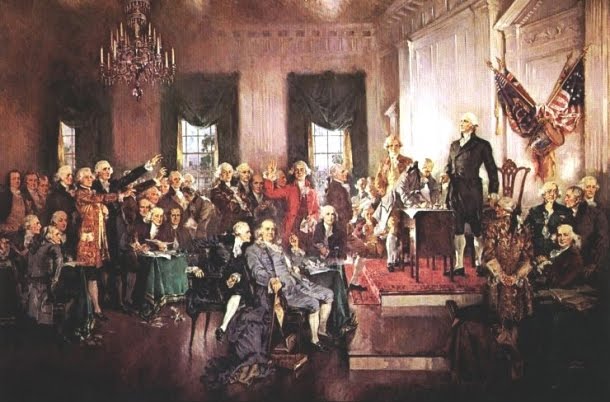

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment