From The CATO Institute:

Let’s Not Blame Immigrants for High Unemployment Rates

By Stuart Anderson, an adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute and executive director, National Foundation for American Policy.

Given the current high unemployment rates in America it is predictable that some seeking to cast blame are calling on America to “round up the usual suspects,” in the words of Captain Renault in the movie Casablanca. Throughout American history, immigrants have been among the usual suspects when looking for culprits in times of economic trouble. However, an understanding of how immigrants function in the labor market and an examination of the likely causes of high unemployment rates illustrate why the foreign-born are not at fault for unemployment in America.

Immigrants and Jobs

The fallacy that drives most discussions of the impact of immigrants on natives is that only a fixed number of jobs exist, which would mean any newcomer must take away jobs from natives. Mark J. Perry, a professor of economics and finance in the School of Management at the Flint campus of the University of Michigan, dispels this myth: “There is no fixed pie or fixed number of jobs, so there is no way for immigrants to take away jobs from Americans. Immigrants expand the economic pie.”1

While immigrants fill jobs, they also create jobs in a variety of ways, explain economists Richard Vedder, Lowell Gallaway and Stephen Moore:

First, immigrants may expand the demand for goods and services through their consumption. Second, immigrants may contribute to output through the investment of savings they bring with them. Third, immigrants have high rates of entrepreneurship, which may lead to the creation of new jobs for U.S. workers. Fourth, immigrants may fill vital niches in the low and high skilled ends of the labor market, thus creating subsidiary job opportunities for Americans. Fifth, immigrants may contribute to economies of scale in production and the growth of markets.2

Vedder, Gallaway and Moore, a former Cato Institute economist, completed research on the 10 states with the highest and lowest concentration of immigrants for the period 1960 to 1990. They found, “In the 10 high-immigrant states, the median unemployment rate in the 1960–91 period was about 5.9 percent, compared with 6.6 percent in the 10 low-immigrant states.” They also discovered that between 1980 and 1990, “The median proportion of the population that was foreign-born was 1.56 percent in the high-unemployment states, compared with 3.84 percent in the low-unemployment states. More immigrants, lower unemployment.”3

In his book, Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in the Twentieth Century, Richard Vedder and his coauthor Lowell Gallaway found, “no statistically reliable correlation between the percentage of the population that was foreign-born and the national unemployment rate over the period 1900–1989, or for just the postwar era (1947–1989).”4

In a recent analysis for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, economist Giovanni Peri also concluded immigrants helped, rather than hindered, both natives and the U.S. economy. “Statistical analysis of state-level data shows that immigrants expand the economy’s productive capacity by stimulating investment and promoting specialization. This produces efficiency gains and boosts income per worker. At the same time, evidence is scant that immigrants diminish the employment opportunities of U.S.-born workers.... There is no evidence that immigrants crowd out U.S.-born workers in either the short or long run.”5

The Likely Causes of Persistent U.S. Unemployment Rates

The unemployment rate in August 2010 was 9.6 percent, which remains high by U.S. contemporary standards.6 As recently as 2007, the average annual U.S. unemployment rate was 4.7 percent.7 In the intervening three years there have been no major changes in immigration policy and, in fact, both the level of illegal entry and the number of applications filed for skilled foreign nationals have decreased in the past year or more.8

If immigrants are not the cause of today’s higher than normal unemployment rate, then what are the likely reasons the U.S. job market has not bounced back? Economists with a free market perspective point to three likely reasons the unemployment rate has not fallen in the past two years: the continued extension of unemployment insurance coverage, the large increases in the federal minimum wage, and anticipated future business costs, including taxes and health care mandates.

If you tax something, then you’ll get less of it, and if you subsidize something, you’ll get more of it. If policymakers appreciated these two economic rules they would seldom be surprised by the outcome of their decisions. In the case of unemployment insurance, it is ironic that those whose political and policy fortunes have been most tied to the desire for a lower unemployment rate likely have contributed to a higher national unemployment rate through unfortunate choices.

The U.S. Congress, with the support of the Obama Administration, has expanded the eligibility for unemployment insurance from the traditional 26 weeks of coverage to the unprecedented level of 99 weeks. That means while in the past after 26 weeks an unemployed person might choose to take a job for lower pay, the same individual could instead afford to wait due to a government guarantee of income. In effect, this has artificially raised the wages an employer must offer to hire that individual—and the wages may be higher than an employer believes are affordable. This creates a related problem: the longer someone remains without a job, the less desirable that individual may become to employers. Multiply this circumstance by hundreds of thousands or even millions of people and it can cause the unemployment rate to be higher than it would be without the many additional weeks of unemployment insurance coverage.

In a recent op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, Harvard University economics professor Robert Barro discussed how the expansion of unemployment insurance eligibility has upended the previous policy balance and has led to at least a perceived Western European–style entitlement for many workers: “The unemployment-insurance program involves a balance between compassion—providing for persons temporarily without work—and efficiency. The loss in efficiency results partly because the program subsidizes unemployment, causing insufficient job-search, job-acceptance and levels of employment.”9

Barro compared long-term unemployment rates and duration of joblessness for different periods in U.S. economic history. “The duration of unemployment peaked (thus far) at 35.2 weeks in June 2010, when the share of long-term unemployment in the total reached a remarkable 46.2 percent. These numbers are way above the ceilings of 21 weeks and 25 percent share applicable to previous post-World War II recessions. The dramatic expansion of unemployment-insurance eligibility to 99 weeks is almost surely the culprit.”10

Table 1 illustrates a hypothetical alternative level of unemployment if unemployment insurance had remained at 26 weeks, rather than being expanded to 99 weeks. Barro writes:

To get a rough quantitative estimate of the implications for the unemployment rate, suppose that the expansion of unemployment-insurance coverage to 99 weeks had not occurred and—I assume—the share of long-term unemployment had equaled the peak value of 24.5% observed in July 1983. Then, if the number of unemployed 26 weeks or less in June 2010 had still equaled the observed value of 7.9 million, the total number of unemployed would have been 10.4 million rather than 14.6 million. If the labor force still equaled the observed value (153.7 million), the unemployment rate would have been 6.8% rather than 9.5%.11

Table 1

Hypothetical Total Unemployment and Unemployment Rate without

Unemployment Insurance Eligibility of 99 Weeks

Actual Estimate Without 99 Weeks of Unemployment Insurance Coverage

Total Unemployed in June 2010 14.6 million 10.4 million

Unemployment Rate in June 2010 9.5 percent 6.8 percent

Source: Robert Barro, “The Folly of Subsidizing Unemployment,” Wall Street Journal, August 30, 2010.

Additional Reasons for Continued High Unemployment

A second reason offered for current high unemployment rates, particularly among younger workers, is the increase in the minimum wage. As George Mason University economist Don Boudreaux explains: “Between 2007 and 2009, Uncle Sam ordered teenage workers (who are mostly unskilled) to raise the price they charge for their labor services by 41 percent. (That is, the federal minimum-wage rose from $5.15 per hour in 2007 to its current level of $7.25 in 2009—a 41 percent increase.)”12

The rise in the minimum wage as a contributing factor in teen unemployment rates is absent in media accounts on the subject. However, economists understand that employers may only find it profitable to hire teen workers at wages lower than the federally mandated minimum, given that such workers often possess few skills and little work experience. If that is the case, then employers will not hire such workers and they will be unemployed (or stop even seeking work).

Don Boudreaux sent a letter to the New York Times, which had omitted the minimum wage increase in an article on teen unemployment. He wrote, “Suppose Uncle Sam orders you to raise by 41 percent the price you charge for subscriptions to your newspaper. Would you be surprised to find a subsequent fall in the number of subscribers? If you assigned a reporter to investigate the reasons for this decline in subscriptions, would you be impressed if that reporter files a story offering several possible explanations for the fall in subscriptions without, however, once mentioning the mandated 41 percent price hike?”13

A third area that likely contributes to unemployment is employers’ uncertainty about future tax and regulatory costs. When a small business owner decides whether he can afford to hire more people, he must calculate not only current costs but also anticipated costs. If tax rates or mandated health coverage costs are expected to increase, then an employer knows less money will be available to expand the business and hire more workers.

Since 2009, Congress and the administration have significantly increased federal spending. Given the deficit, this has led business owners to conclude taxes will eventually need to be increased to account for the additional spending. In addition, within the past year Congress has passed an expensive new health care law that many employers believe will increase both taxes and their future obligated health care costs. A policy of lower spending is more likely to have produced a favorable hiring climate. “Lower spending reduces the fear of higher taxes, which leads to an increase in consumer and business demand and growth,” noted Veronique de Rugy, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.14 She cited research from Goldman Sachs economists Ben Broadbent and Kevin Daly on the negative impact of large-scale increases in government spending on a cross-section of economies.

Conclusion

Immigration is not the cause of today’s high unemployment rates. In fact, reliable estimates show that immigration levels—both illegal immigration and applications for H-1B visas for high-skilled professionals—have fallen along with the economic downturn.15 It makes no sense for members of Congress to attempt to lower the level of immigration to address poor choices made in economic policy. Such members should recall what Julius Caesar told Brutus: “The fault, dear Brutus, lies not in our stars, but in ourselves.”

1 Interview with Mark J. Perry in Stuart Anderson, Immigration (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2010), p. 169.

2 Richard Vedder, Lowell Gallaway and Stephen Moore, Immigration and Unemployment: New Evidence, Alexis de Tocqueville Institution, Arlington, VA (March 1994), p. 2, as cited in Stuart Anderson, Employment-Based Immigration and High Technology (Washington: Empower America, 1996), p. 66.

3 Richard Vedder, “Immigration Doesn’t Displace Natives,” Wall Street Journal, March 28, 1994.

4 Ibid.

5 Giovanni Peri, “The Effect of Immigrants on U.S. Employment and Productivity,” FRBSF Economic Letter, 2010–26, August 30, 2010.

6 Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor.

7 Ibid.

8 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; Josh Dulaney, “Illegal Immigration Drops,” Contra Costa Times, September 12, 2010.

9 Robert Barro, “The Folly of Subsidizing Unemployment,” Wall Street Journal, August 30, 2010.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Don Boudreaux, “Crack Reporting,” Café Hayek (blog), June 1, 2010.

13Ibid.

14 Veronique de Rugy, “Austerity Agonistes,” Reason, October 2010, p. 21.

15 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Dulaney.

Click here to download the September 2010 Immigration Reform Bulletin (PDF).

A READER ON THE STATE OF THE POLITICAL DECAY AND IDEOLOGICAL GRIDLOCK BETWEEN ONE GROUP WHO SEEK TO DESTROY THE COUNTRY, AND THOSE WHO WANT TO RESTORE IT.

The Rise and Fall of Hope and Change

Alexis de Toqueville

The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

The United States Capitol Building

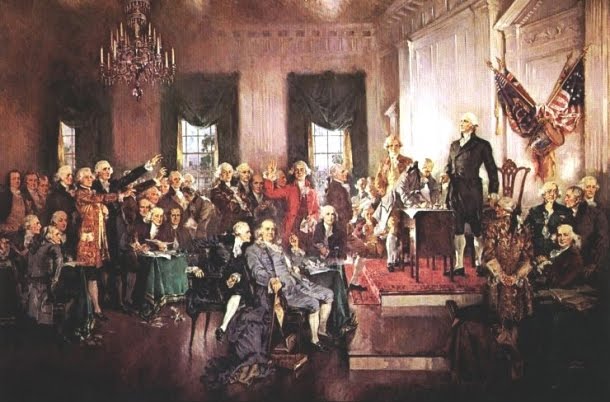

The Constitutional Convention

The Continental Congress

George Washington at Valley Forge

No comments:

Post a Comment