From CFIF:

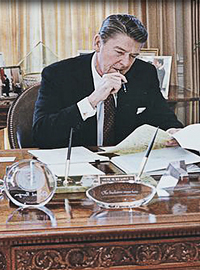

| Reagan 101 |  |

| BY QUIN HILLYER THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 02 2012 |

A year ago the conservative movement was fired up for a year-long celebration of Ronald Reagan’s 100th birthday. Well, it didn’t really last a year, but this coming Monday, February 6, the Gipper would have been 101, and the longing for comparable conservative leadership will not disappear just because his centennial has passed. Indeed, that longing grows ever more intense as this frustrating presidential primary season lurches forward. It’s too bad, then, that so many myths, from both left and right, cloud the true Reagan legacy. Myth Number One, from both sides, is that Reagan was some sort of hard-line conservative ideological purist. That’s absurd. Reagan was well enough rooted in conservative theory, including Eric Hoffer’s work, to abjure ideology. Reagan had a political philosophy, not an ideology. Part of that political philosophy, eminently Madisonian, was a belief in the efficacy of the practice of politics in a society of ordered liberty. Public persuasion, principled advocacy and, yes, the art of negotiation were all to be employed in pursuit of implementing conservative beliefs. Reagan was hardly the sort of man to fall over the side of a cliff while in the throes of quixotic insistence on perfect legislation. Hence, for instance, the final shape of Reagan’s famous 1981 tax cuts. Originally Reagan wanted a clean, 10 percent-per-year reduction in marginal rates for each of three years. The votes in Congress, however, weren’t there for that clean proposal. In the end, Reagan accepted numerous special-interest tax breaks -- “Christmas tree ornaments,” some of them soon repealed in the1982 TEFRA Act – to entice votes for his plan. He also was forced to scale back the first-year rate cut from 10 percent to 5 percent, even though he felt sure the delay would retard the economic recovery the bill was supposed to catalyze. Perfection wasn’t attainable. As Reagan used to remind people, “the purpose of a negotiation is to get an agreement.” What Reagan understood is that one successful negotiation can lead to another. The 1981 tax cuts, which set a top rate of 50 percent, weren’t the end of his striving. By the end of 1986, he had helped shape a tax code with top rates all the way down to 28 percent. He showed that the process works – the whole process, played out in multiple years in a system designed to move slowly. Myth Number Two, pushed by both sides, is that Reagan failed at achieving budgetary savings. The truth is that he failed only on the entitlement side, mainly by inheriting formulas for growth that were made evermore overgenerous by Johnson, Nixon and (to some extent) Carter. On domestic discretionary spending, Reagan was a champ. Total non-defense discretionary budget authority, 1981: $160.516 billion. Total non-defense discretionary authority, 1989: $171.013 billion. What that amount would have been in 1989 if it merely had kept up with inflation (not even counting population growth or built-in “baseline adjustments): $218.97 billion, or nearly $48 billion more expensive than Reagan actually achieved. Because the intervening years included actual-dollar cuts, the aggregate amount saved compared to inflation growth was on the order of more than $300 billion in eight years – a stunning amount, equivalent in today’s dollars to about $800 billion. The lesson there is that patient firmness can indeed achieve federal budgetary discipline. Myth Number Three, pushed (alas) by conservatives, and at least in public by Reagan himself, was/is that it was the content of Reagan’s message – the particular political beliefs – rather than the delivery of them, that so often won the day. As Reagan said, “I wasn't a great communicator, but I communicated great things… from the heart of a great nation.” In other words, conservative principles are so deeply held by an American majority that the principles themselves are necessarily political winners. This is a reaction against the leftist myth that Reagan was merely a great communicator whose delivery fooled the public into supporting Reagan despite his policies and principles. The truth is in between. The reality was that many of the policies Reagan pushed were anything but self-evidently popular, but also (contra the liberal myth) that they weren’t inherently unpopular either aside from Reagan’s supposed ability to bamboozle people. Instead, Reagan fought – long, relentlessly and often in the face of ridicule – in that great middle ground where the public’s mind is unsettled and uncertain. The principles didn’t win on their own; they needed to be crafted, polished, carefully and cheerfully and exhaustingly explained, before they would emerge triumphant. What far too few politicians do today is to work hard at making both an art and a craft of communicating great things. Persuasion isn’t mere rhetoric; persuasion takes serious labor. Ronald Reagan did not shy from that labor. That’s why he communicated greatly: He melded his excellent principles with the persuasive skills gained from long striving. They were complementary assets. Without each and both of them, he would not have succeeded. |

No comments:

Post a Comment